With Ridley Scott’s Napoleon thundering over the horizon on horseback, time to haul out a movie Scott and his star Joaquin Phoenix have clearly feasted on, 1927’s historic and historical behemoth, Napoleon, aka Napoléon vu par Abel Gance (ie “as seen by Abel Gance”).

Adored by Coppola, derided by Kubrick, who thought it “really terrible” though technically a masterpiece, the movie clearly divides opinion but is required viewing by anyone with an interest in the Corsican general who conquered Europe or the silent films of a century ago. Whatever you think of it, you’ll get a dry laugh from reading the one-line synopsis on the IMDb – “A film about the French general’s youth and early military career”. Because the film as it stands is five and a half hours long. Five and a half hours to squeeze in Napoleon’s “youth and early military career” – oh, we’ll manage somehow. If that’s not enough for you, there’s a seven-hour version somewhere in the works.

Gance spends the first half hour of the movie at a snowball fight in Napoleon Bonaparte’s schooldays, where the highly unpopular Bonaparte (too insular, haughty and Corsican) first exhibits leadership qualities. From here it’s on to the French revolution nine years later, a sojourn back in Corsica where Bonaparte persuades the islanders to embrace French rather than British or Italian rule. Back to France, where the revolutionary guillotine is busy, and then on to the Siege of Toulon, where Bonaparte is finally recognised for the strategic genius he was. A pause in the ascent as he struggles in poverty, before Bonaparte becomes the man who saves the revolution from itself, woos and wins high-born Josephine and sets off for Italy and further conquest.

Watching this film is like reading a long and detailed history book with extensive footnotes, appendices and a thick index. When the action shifts to Corsica, an intertitle tells us that the scenes were shot in the actual Corsican locations. Because of the vast length, dramatic compression, poetic licence and storytelling flair are not in great demand, though it’s obvious that Gance does have a keen visual and theatrical sense – the shot at the Siege of Toulon where Bonaparte and a general argue in the torrential rain, oblivious to the weather, is urgent and incisive. If only there’d been a bit more of this sort of thing.

Gance makes up for it with technical fireworks. This is an astonishingly modern movie packed with innovative technique. In an era when cameras were generally locked down on a static tripod, Gance’s is fluid, often handheld, the looseness accentuated with rapid, action editing, overlays and dynamic pans. There are dramatic close-ups, whole sections with tinted colours, cross-cutting, split and multiple screens, vertiginous lunges into space (the camera is on a rope, presumably), impossible and impossibly fast tracking shots. At one point there are seven, maybe more, overlaid shots competing for screen space. At another Gance pushes the lighting into a very high key. At yet another he puts so much romantic soft filtration on the lens that the image becomes impressionistic. Most impressive of all, when the action eventually shifts to the Italian campaign, Gance goes widescreen, using three separate cameras side by side to create an epic composite. You can see the joins – and Gance occasionally plays to those joins with three separate images – but it’s magnificent all the same, Cinerama decades before it would be invented.

Gance is a master of the crowd scene. The battles are brutal and brilliantly choreographed – horses charging across the plains, soldiers drowning in mud – but so are the scenes set in revolutionary Paris, where mob rule is always on the verge of breaking out.

Gance’s Bonaparte is the Great Man theory of history incarnate. He’s also, in Gance’s view, the godfather of the European Union – “Europe will become a single people!” Bonaparte declaims at one point. This is Bonaparte as a force for good, spreading the liberalising ideals of the Revolution through Europe. The one that Beethoven dedicated his Eroica symphony to (later to regret it, but that’s another story).

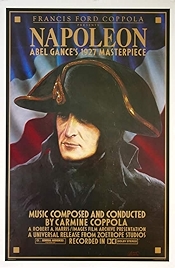

Beethoven features heavily, almost exclusively, in the stirring, titanic score put together by Carl Davis. It’s the one you’ll be listening to if you’re watching the BFI version of the movie (linked to below), the summation of about 50 years of Herculean work by film historian Kevin Brownlow. There have been previous restored versions of Gance’s Napoleon, most notably two in 1980 (one with a score by Carmine Coppola, the other by Davis) and 1983. The BFI one, the longest to date, is from 2000 (it was digitally cleaned up in 2016). If the seven-hour one ever materialises, will newer digital techniques improve what’s already a very fine image?

It’s a folie de grandeur no matter how you look at it, but even more so when you realise Gance intended his vainglorious movie to be the first of six. The failure at the box office of his opening instalment put paid to that idea. Never mind six leviathans, this first one was not just too long, it was too difficult to screen (three projectors were required for the final section) and it debuted at exactly the moment when silent movies were being overtaken by the talkies. Even cut down to around 110 minutes it didn’t do well in the USA.

Looking at the trailers for Ridley Scott’s Napoleon, it’s clear that Joaquin Phoenix is partly modelling his Bonaparte on Albert Dieudonné’s impressively imperious one. The flashing eyes and fervour of Dieudonné make his performance absolutely the one to beat. When he died in 1976, aged 86, having acted in barely anything else in the intervening decades, Dieudonné was buried in his Napoleon costume. He lives on in this mad, glorious movie.

Napoleon aka Napoléon vu par Abel Gance – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2023