Arthur Penn’s 1975 movie Night Moves sits snugly alongside two other films made about the same time – Polanski’s Chinatown (which went into production in the same month in 1973) and Altman’s The Long Goodbye, which had opened earlier that year. All three are neo-noirs recalling the era of Raymond Chandler, Sam Spade and Humphrey Bogart.

Of the bunch only Chinatown was a proper box office and critical hit, and even then some critics were a bit sniffy (the New York Times didn’t go a bundle). Since then, The Long Goodbye has been rerated upwards to join Chinatown in the pantheon, and now it looks like Night Moves is also in the process of being re-appraised (though Roger Ebert wasn’t alone in praising it to the skies on its release).

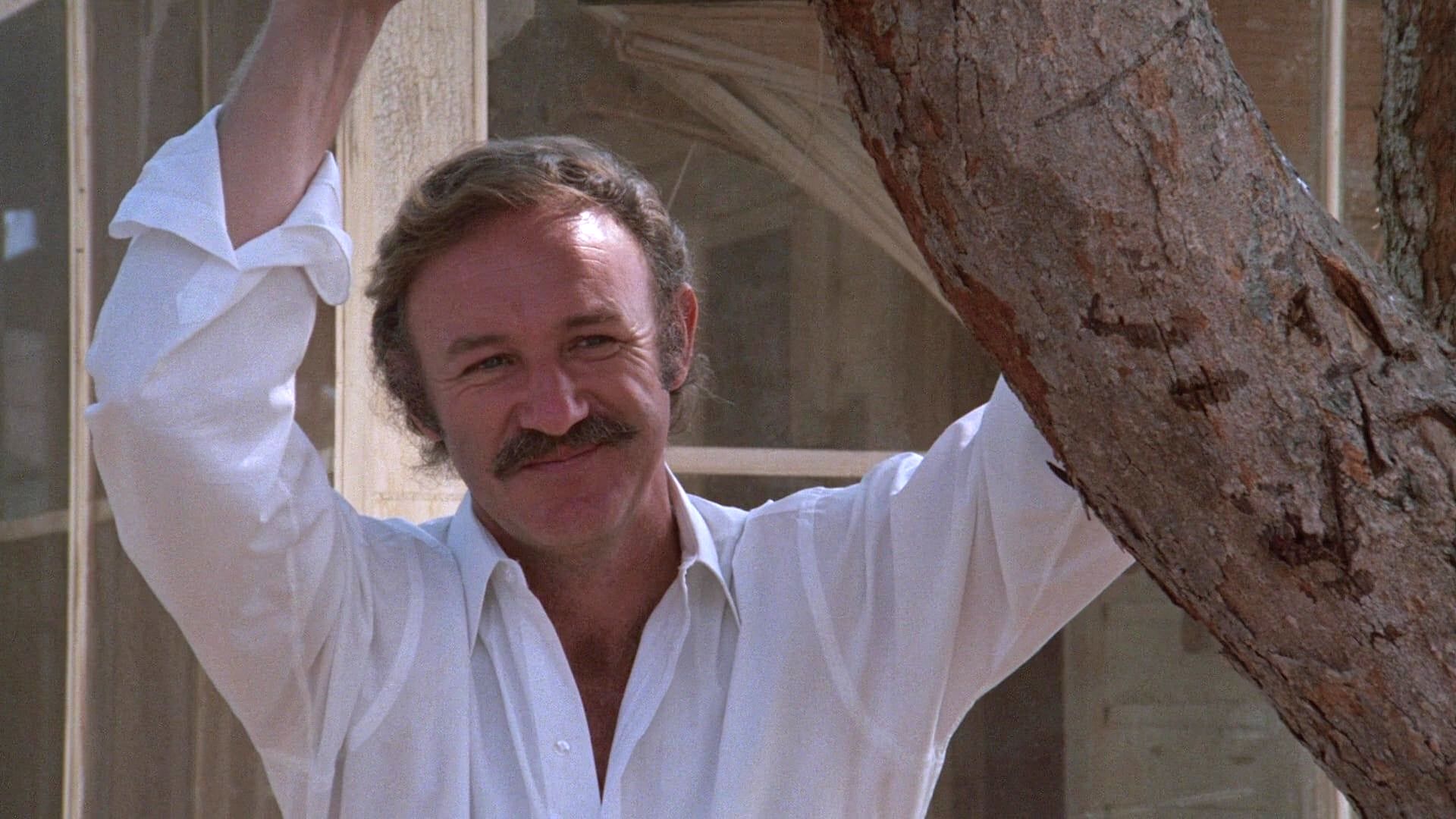

In terms of plot and character there really isn’t much to see here, or nothing new at any rate. Gene Hackman plays Harry Moseby, a jaded private detective hunting for the missing teenage daughter of a retired Hollywood actress. It’s precisely the sort of case that Philip Marlowe might have taken back in the 1940s. And in many ways Harry is the successor of Marlowe’s white-knight good guy walking the mean streets described by Raymond Chandler.

The client slots right into the groove too, being a boozy floozy more interested in bedding men than having her daughter found. As to the daughter, she’s jailbait and Harry’s method of tracking her down is to work his way backwards through the chain of men who have taken advantage of this 16-year-old who has inherited, Harry notes, her mother’s once-great tits.

Not much to see here, maybe, but with about 30 minutes of running time still to go – case solved, girl heading home with Harry – the plot dives off up an unexpected avenue and suddenly this downbeat noir is exploding with stunts, gunplay, on-screen death and a spectacular bit of action. Almost as if director Arthur Penn were aiming to recreate the effect of his biggest hit to date, Bonnie and Clyde, and its bullet-riddled down-curtain.

But even with the maxed-out ending, this is a film that’s not setting out to wow us with its plot. It’s more of a mood thing, one established completely the moment Gene Hackman’s Moseby first appears, a former football pro turned old-school PI with charm, a smart mouth and woman trouble.

Penn gives us atmosphere, thick and warm and a bit dog-eared – the office that’s seen better days, the ageing starlet ditto, the beat-up car Harry drives – especially once the action shifts down to Florida, where the missing Delly is hanging out with her stepdad and his woman Paula (Jennifer Warren), who catches Harry’s eye.

The casting is an interesting mix of people who act well and ones who don’t. Warren struggles, so does Janet Ward as the missing girl’s mother (but then she is meant to be playing an actress who was never much good). Edward Binns, as something in the movie biz, also struggles to create a credible character. Maybe it’s Alan Sharp’s screenplay. Maybe it’s the ever-present comparisons to Raymond Chandler.

There is a young James Woods as a wiry, spiky mechanic who’s one of Delly’s conquests. And a very young Melanie Griffith, in her first screen role, as cockteasing Delly, a girl permanently eager to show the world what she’s got. Griffith was 16 when the film was made and production was paused so she could grow up a bit (legal reasons, I’m guessing). The nude scenes that dot Night Moves were shot right before it was released, over a year after the rest of it.

The title, incidentally, is a play on Knight Moves, a reference to a 1922 chess game famous for the play that the loser didn’t make and which would have won him the game. Here’s how it should have gone, Harry shows Paula at one point, and then shows her again, reinforcing the point. That’s the mood of this film – one of disappointment, the unhappy ending. Anyone fancy a bit of psychological read-across to post-Watergate America?

Night Moves – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022