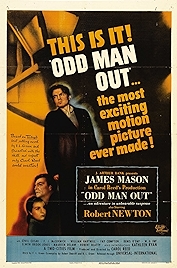

The tragedy is Greek but the accents are Irish in 1947’s Odd Man Out, a day in the death of a wounded Republican man on the run in Belfast. The film turned James Mason from a British star into an international one and is often rated as director Carol Reed’s best film. Peckinpah loved it. Polanski also. Mason thought it was the best thing he ever did.

An opening statement declares that this isn’t really about partisan struggle in Northern Ireland, where Republican Catholics were engaged in a long struggle against Protestant Unionists. And, true to their word, director Carol Reed and writers FL Green (he also wrote the book the film is based on) and RC Sherriff never use the word Republican, never openly state that it’s the workings of the IRA that we’re watching, barely engage at all with the everyday political nitty gritty of the situation, allowing a portrait to develop of human frailty and human foibles that’s more universally applicable.

After setting everything up nicely with a thumbnail sketch of the main character – Johnny, the IRA cell leader with serious qualms about the role of violence in the struggle – the story plays out in the aftermath of a heist gone wrong, which resulted in the death of a cashier and gang leader Johnny receiving a mortal bullet wound himself. Now, on the run in the city, Johnny staggers from one potential hiding place to another.

The film is composed of a series of vignettes. Encounters with everyday folk, you could say, the sort of people who aren’t involved in the struggle for political change and just want to be left to get on with their own business. A courting couple blundering into Johnny’s hiding place, the kids on the street taunting the police, a shebeen run by a grand old chatterbox, on board a tram to the Falls Road, a beautiful old bar where Johnny also takes refuge. And there are more extended character sketches – the “bird man” (FJ McCormick) trying to “help” Johnny by shopping him to the police for the reward money. The kindly local priest, Father Tom (WG Fay). Gin (Joseph Tomelty), the cabbie unaware that he’s got the wounded man in his cab. A floridly bohemian artist (Robert Newton, as madly entertaining and flamboyant as ever) who wants to sketch the dying man.

Kathleen Ryan holds it all together as the young woman sweet on Johnny and moving between all these people and places, and encountering the police (in the shape of Denis O’Dea) at every turn. It’s Ryan who makes it a story rather than just a series of events and it’s her love for Johnny that gives the film a shape, of hope. Perhaps Johnny will make it after all. Perhaps he will…

As Johnny drifts from being very badly hurt to the edge of death, DP Robert Krasker keeps the stygian imagery coming. It’s a starkly shot film, much of it on the streets of Belfast, where Krasker’s love of back lighting and shadowy confined spaces emphasise Johnny’s plight.

Mason’s performance is really a series of deathbed scenes but he does manage to inject a bit of variety into what is little more than a series of wounded looks and pained groans, with the odd feverish hallucination giving Mason a chance to do some actual acting.

Less successful are the other actors and in particular Reed’s decision to use a lot of players from the Abbey Theatre in Dublin as his cast. There is nothing wrong with the actors themselves. In fact they’re a remarkable bunch and there isn’t a bad apple among them. But there is a painful lack of actual Belfast accents in this, unless you count the street kids, and far too many from south of the border. And this sort of thing matters. In Reed’s defence we go back to his initial statement, that this isn’t really about… what it obviously is about.

The lack of heroics in Johnny’s gang adds to the sense that there is after all a political position being taken here, for all the declarations to the contrary. These guys are a bunch of incompetents who fall into terrible in-fighting the minute their leader is out of the picture. The British police, by contrast, are stern but fair. FL Green’s original novel apparently was a lot more politically inclined and far more scathing about the IRA.

In the end it’s the ancient Greeks not the modern Irish that this is about. Greek tragedy’s “three unities” of time, place and action are adhered to, since this is a story told in one time (a day), one place (the streets) and to one person. Johnny even has the Greek hero’s tragic flaw – not listening to the promptings of his heart when he embarked on the heist in the first place. Now he is paying with his life. And as he limps towards the docks in the film’s closing scenes, with Kathleen accompanying him on his journey towards the next stage of his life, a ship hoots balefully, and later hoots again, in the dark, like Cerberus barking at the gates of Hades.

Odd Man Out – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2023