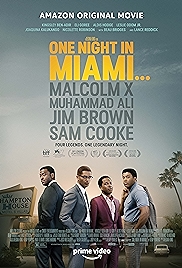

What did Muhammad Ali, Sam Cooke, Jim Brown and Malcolm X all talk about when they met to celebrate on the night of Ali’s victory over Sonny Liston in January 1964? It’s a fascinating question that One Night in Miami asks.

The answer, in reality, is nothing, since the meeting never took place. But Kemp Powers’s play imagined that it did, and it didn’t do the box office any harm. Now Regina King’s silky and understated direction brings it to a wider audience.

Ali wasn’t called Ali back then. He was still using his birth name, Cassius Clay, a fact that boomers will already know since Ali is part of their programming. For younger audiences, we’re introduced to the four key figures in swift vignettes that catch each of them at a low ebb. Clay is being knocked down by British boxer Henry Cooper, Brown is being racially disrespected, Malcolm X is struggling with his membership of the Nation of Islam and Cooke is playing the Copacabana nightclub, to the indifference and hostility of its white audience.

King does not hang around here but even so manages to give us a sense of who the boxer, NFL legend, political activist and singer are, if we didn’t already know. A familiar TV face acting in series such as Watchmen, and Southland, King has been steadily building a parallel career as a director over the last ten years.

One Night in Miami marks her coming of age in the field. As with many actors who take up directing, she works well with her on-screen talent – Eli Goree as the loud and proud Cassius Clay, Kingsley Ben-Adir as forensic and slightly stick-up-ass Malcolm X, Aldis Hodge as dignified but wounded Jim Brown and Leslie Odom Jr as smart and sweet-voiced Sam Cooke.

At Malcolm X’s behest the three other guests meet for what they imagine is going to be a post-fight pussy party. But they’re shocked to discover that there’s no booze – Malcolm is a Muslim of a strict and particular sort – and only vanilla ice cream as refreshment.

You might expect Clay to hog the film. But though Eli Goree’s Clay is a brilliant thing to watch – the bragging, the cheekiness, the smarts, the performative nous – the weight of the drama is with Malcolm X and Sam Cooke.

What Powers’s play wants to hash out is the same stuff as the film The Butler went over – gradualism versus revolution as a way of improving the lot of “the negro” in America. Cooke, not just a pop star but the owner of his own master tapes and a canny businessman with his own label, is the gradualist; Malcolm X, sharp as a laser and with a mouth that could level mountains, is all for revolution and in this struggle you’re either with him or against him. As the night wears on, Malcolm wheedles away at Sam, trying to find the killer argument that will convince him, while Clay and Brown act as palate cleansers between bouts.

Though the intros are handled with economy, things slow down after that and One Night in Miami only really start to cook at about an hour in, after all the intros and smalltalk have been got out of the way and when the argument between Malcolm and Sam gets more personal and heated.

Nit-pickers, pedants like me, will flinch at the use of anachronistic language – no one in 1964 used “reach out” meaning to make contact, similarly the “black community” and “you do the math” were still a good way in the future.

But what great performances, both as individuals and as an ensemble, with the bonus of Leslie Odom’s Jr’s remarkable mimicry of Sam Cooke’s sweet singing voice, and that is a hard voice to mimic.

It never looks like it isn’t a stage play, and Regina King works with that, using the sense of place, of atmosphere and tension to craft an immersive experience. Not quite as if you were in the room with this awesome foursome, but close.

One Night in Miami – Watch it/buy at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2021