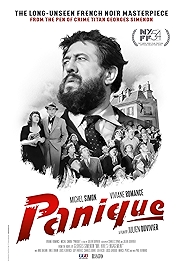

How’s this for grim! The atmospheric and technically superb Panique, released in 1946, one year after the war ended, gave the French people an image of themselves at their worst. What the domestic market wanted at the time was sugar-coated triumphalism, stories about the nobility of the Resistance to the German occupation and the endurance of the indomitable French spirit etc. Unsurprisingly the film bombed.

An adaptation of one of Georges Simenon’s “romans durs” (the tougher novels that didn’t feature Simenon’s decent detective Maigret), it opens with the death of a woman and closes with the death of a man. In between director/co-writer Julien Duvivier gives us one of the most relentlessly depressing portraits of human behaviour – both individual and en masse – ever committed to screen.

The “heroes” are a threeway love triangle consisting of the murderer, Alfred (Paul Bernard), his scheming femme fatale lover Alice (Viviane Romance) and the local weirdo, the creepy Monsieur Hire (Michel Simon), a phoney clairvoyant and sexual deviant (it’s hinted), who falls badly for Alice and believes he can separate her from Alfred by pointing out to her that Alfred is the murderer and that he has evidence to prove it.

Barely breaking stride, Alice rapidly shifts tack, swapping out the revulsion she feels for Hire with a phony, coquettish display of suggestive sexuality – touching her blouse, the hem of her skirt – designed to buy her and Alfred time until they can work out how to deal with Hire and make good their escape.

These are the good guys.

Against them are the townsfolk, a small-minded rabble keen to level accusations, create scapegoats and use any opportunity to get a lynchmob assembled. Chief among them are the loudmouth town butcher, the self-important local tax official and a brassy streetwalker, all of them high on their own opinion of themselves and keen to pin the murder on the most obvious candidate – Monsieur Hire.

The beauty of Simenon’s original story is the way these two prongs – the threeway of Alice/Alfred/Hire and the Hire/townsfolk strand – feed into each other and eventually become one, at which point Monsieur Hire is running for his life over the rooftops while a mob bays below in a finale with echoes of The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

There’s are reminders of Fritz Lang’s M in Panique’s dissection of mob behaviour, and also in Duvivier’s superb technique – the fluid cranework, the way Duvivier’s clever camera dissolves between exterior and interior while also making us keenly aware of what different realms they are. The deep-focus cinematography and stark lighting of the brilliant Nicolas Hayer (who worked with plenty of greats, including Clouzot, Cocteau and Melville).

It’s a film full of great faces – Michel Simon, the big bear of a man (who most might remember in the Burt Lancaster movie The Train). And evocative locations. The bar, the butcher’s shop, the garage where Alfred works (in his suit!), rooming houses, a carnival, a wrestling match, the streets, all of which look like Duvivier is warming them up for Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch, if Anderson ever decided to go to the dark side.

Duvivier did not like happy endings and saw his films as a corrective to Hollywood’s tendency to go for them. Unlike his La Belle Equipe, which was reshot with a happier ending, against Duvivier’s wishes, Panique’s ending is bleak, and then gets bleaker still, fading out on Alice and Alfred on a merry-go-round having a moment of escape, unaware that the police are waiting to arrest them the minute the ride comes to halt.

In a long career during which he took on many genres – which counted against him when the New Wavers started writing their “who’s hot, who’s not” lists – Duvivier considered this to be his best film, trumping even the much more fancied Pépé Le Moko.

Panique – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022