One of three 1970s thrillers Alan Pakula directed in quick succession, The Parallax View is sandwiched between two better films, Klute (1971) and All the President’s Men (1976), the second leg of what’s now known as his “paranoia trilogy”.

Posterity is in the process of polishing The Parallax View’s reputation, with the focus usually on two aspects: the cinematography of Gordon Willis and the conspiracy at the centre of it, which is not, for once, all a big government put-on. Instead it’s a big bad company, the Parallax Corporation, that’s pulling the strings by seeking out unstable individuals and then grooming them for political assassinations. Don’t tell Ayn Rand.

Loren Singer’s original novel centred on the assassination of John F Kennedy but this adaptation (David Giler and Lorenzo Semple Jr) turns the receiver of the bullet into a reasonably nondescript politico, William Joyce playing the lean, handsome independent senator who jokes that he’s “probably too independent for his own good” before he is killed on a meet-and-greet in a way that would have reminded audiences of the day of the death of JFK’s brother Robert.

Things get going properly when no-mark reporter Joe Frady (Warren Beatty) gets wind of the fact that people who were there on the day of the assassination are dying one after another in mysterious ways. Someone is eliminating all the witnesses – they’ve obviously seen something, even if they don’t know that they have.

In conspiracy thriller style, Frady goes to work, following the trail from low-level operatives upwards until he’s infiltrating the Parallax Corporation itself, using himself as a honey trap by posing as just the sort of psychopathic loner that an organisation seeking trainee killers might want to recruit.

While Pakula is many things, a director of action isn’t one of them, and there are two examples of that in this film, one up at a dam where a dodgy redneck lawman and Frady face off. Here, Pakula tries to pull off a Hitchcock set piece and gets just about everything wrong, from lens choices to edits. Later there’s a car chase that is also spectacularly inept.

But he is good on interiors, where the stygian lighting of Willis, not for nothing known as “the Prince of Darkness”, comes into its own. Abetted by Michael Small’s soundtrack, which usefully winds faintly Hitchcockian strings into an otherwise generically 1970s thriller-ish score, a tense mood is generated and maintained.

Frady is an interesting character, a conspiracy theory agnostic only reluctantly persuaded over time that something rum is going on. For the bulk of the movie he’s the blank screen on which the conspiracy plays out. Beatty doesn’t attempt to play him as anything other than the useful idiot following a trail he doesn’t initially believe is leading anywhere, until he’s dumb-lucked himself into full knowledge of what’s going on.

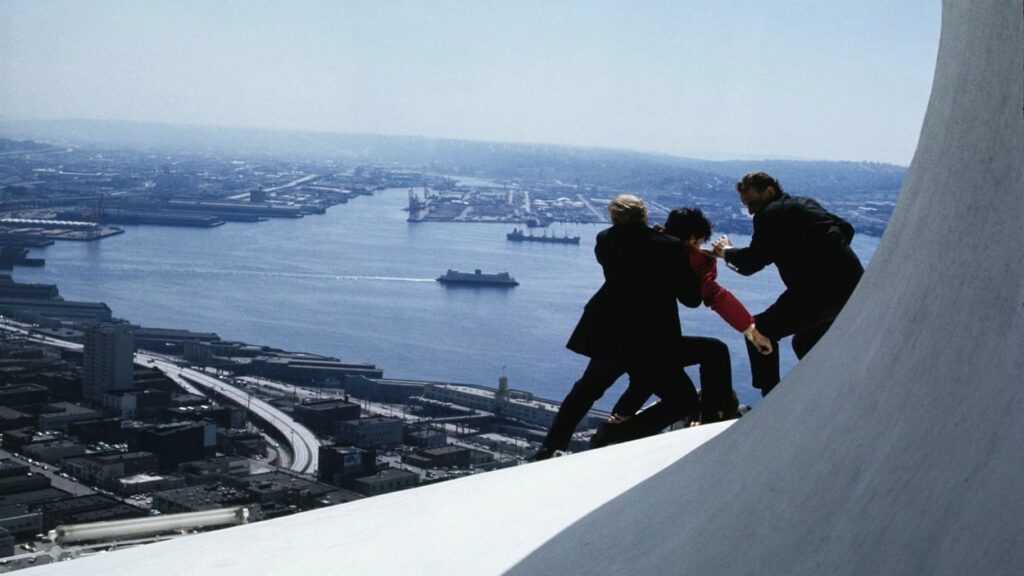

It’s a bleak film that builds powerfully in its final section, which combines Willis’s super-dark interiors, as Frady stumbles about in the gantry space of a massive political convention centre. Meanwhile, on the conference floor, Pakula keeps shooting from a distance and pulled back – so much of this film is shot on long lenses to give the impression of surveillance. The camera is a cool observer (much like Frady) watching what’s going down as another politician gets ready to make his entrance and history is or is not about to repeat itself. It’s another Hitchcock set piece, and this one works.

Perhaps hoping that, in Raymond Chandler style, the actual whys and wherefores of what’s going on don’t all need to be explained, the central section of the film – Frady bumbling about – is a little soft. Chandler gets around this sort of problem with sparkling repartee, but Lorenzo Semple Jr and David Giler are hoping that Beatty’s charisma alone will fill the gap.

Nothing wrong with Beatty, who is rather good as the journalist out of his depth, kept going by his own assessment of what’s going on and his own ability to deal with it – mistaken on both counts. Smug is something Beatty has never had a problem playing. But it’s not enough to plug the gap.

Regularly described as the defining paranoid thriller of the 1970s, The Parallax View either lacks the killer reveal to make it truly satisfying, or is satisfying precisely for that reason – because it keeps some details obscure. Perhaps it just depends on how hungry your inner conspiracy theorist is.

The Parallax View – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate