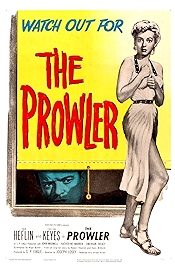

“A masterpiece of sexual creepiness” – writer James Ellroy’s verdict on 1951’s The Prowler, a film that gave two good actors roles of a lifetime and which languished in the pit of obscurity until it was rescued by a restoration in 2011.

The “sexual creepiness” arrives early on. Married woman Susan Gilvray (Evelyn Keyes) calls the cops after seeing what she thinks is a prowler outside her window, peeking at her as she got out of the bath. The cops turn up. No one there. Or is there? One of the policemen, Webb Garwood (Van Heflin), has taken an instant interest in Mrs Gilvray and he returns later that evening, ostensibly just to check everything is OK.

Here come the creepiest scenes in the film. In what’s purportedly an official follow-up visit, Garwood repeatedly shifts from businesslike to over-friendly and insistently oversteps boundaries of behaviour and personal space while Mrs Gilvray tries to re-assert them. Brilliant playing by both Van Heflin and Evelyn Keyes. Then, as a money-shot shorthand for what’s really going on here, Mrs Gilvray offers the cop a glass of milk and he, in his eagerness, almost spills it down his front. Fans of sexual symbolism, fill your boots.

Mrs Gilvray’s husband is a DJ and works at night. She is childless. She is lonely. She’s also loaded, Garwood discovers, having happened upon her husband’s will by accident while looking for a cigarette. If only her husband were dead. A faint echo of the plot of The Postman Always Rings Twice can be heard.

And so off Garwood heads in a sustained bid to possess Mrs G, driven mostly by a simmering resentment at having grown up on the wrong side of the tracks. Garwood might not even be heterosexual, it’s suggested in one vignette, when he’s glimpsed at his place flicking through a muscle magazine.

The roles suit Van Heflin and Evelyn Keyes down to the ground, as if character and actor overlapped. Heflin is a generally unspectacular but reliable actor who never hit the big time. Keyes is an actress whose florid love life got in the way of her career (she was just about still married to John Huston at the time, who is a producer here and got her the gig). It would be easy to confuse Heflin and Garwood – both might want some payback for having put in the hours. And Keyes and Gilvray – a woman who eventually yields when a man makes a real play for her (Keyes’s autobiography, Scarlett O’Hara’s Younger Sister, is more about sexual conquest than acting). The revelation that Mrs Gilvray was an actress before she got married only adds to the suspicion that this overlap is deliberate.

The blacklisted Dalton Trumbo wrote the script, behind the “front” of friend and fellow writer Hugo Butler, and it’s remarkable not just in its deliberate conflation of character and actor but also because the machinations of its serpentine plot – Garwood elaborately wooing, winning, dumping and winning back Mrs Gilvray – reflect the twisted psyche of Garwood, who is thinking like a chess grandmaster about how to get what he wants without suspicion coming his way. And he’d get away with it, too, if fate didn’t deal this couple a crucial card, one that sends them off to a limbo-like ghost town (more symbolism) where a final judgement will eventually be handed down, from the end of a rifle.

The film is sometimes described as film gris, a term coined by academic Thom Anderson, director of the brilliant documentary Los Angeles Plays Itself. Film gris means there’s meant to be some kind of leftist slant. Though it’s hard to see how a bad guy driven by class resentment is any kind of socialist paragon. Nor is Garwood a product of his society – this film teems with decent, hard-working people from just the same background. Garwood is chippy, nasty and devious – hardly the hero and definitely the author of his own misfortune. A sociopath, in short, not a socialist.

It’s also usually described as a B movie, which it is, but there’s A movie talent at work behind the camera – producer is Sam Spiegel (credited as S.P Eagle, geddit), Huston, as mentioned, is a fellow producer, Trumbo is one of Hollywood’s hottest writing properties about this time, blacklisted or not, and the director is Joseph Losey, here on the point of flitting from the USA to escape the McCarthy-era hysteria.

DP is Arthur Miller, who also was cinematographer on How Green Was My Valley and The Song of Bernadette and he really assists Losey’s architectural impulses with stark framings and brilliant tonal control – and the restoration really brings out those dark blacks and crisp whites. James Ellroy gets a credit on the restoration card. He’s also on the commentary soundtrack, and is well worth hearing.

The Prowler – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2023