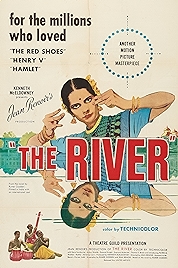

Is 1951’s The River a look in search of a story? It’s regularly described – often by people who haven’t seen it – as one of the greatest films ever made. Dig one layer deeper and the praise heaped on Jean Renoir’s “masterpiece” starts to look a touch more one-note. Martin Scorsese reckons this and The Red Shoes are “the two most beautiful colour films ever made.” Eric Rohmer, also no slouch as a director, called it “the most beautiful colour we have ever seen on the screen.”

The New York Times in 1951 said “beautiful”. Time Out – “beautiful”. Sight and Sound‘s 2022 Best Films of all time poll rang the changes a bit with “lyrical”. There’s nothing wrong with pictorial beauty in itself, but you’ve got to wonder if the focus is on the beauty because there’s not much else to discuss.

To the film itself, which is set in colonial India, where a British family’s idyllic life of being waited on hand and foot is unsettled by the arrival of an eligible white male at the house of their neighbour.

Captain John (Thomas Breen) takes up residence with his uncle, Mr John (Arthur Shields), inflaming the passions of three young women who vie for his attention. Two of them are sisters, vampish Valerie (Adrienne Corri) and younger hasn’t-a-chance Harriet (Patricia Walters), while Mr Tom’s Anglo-Indian daughter, Melanie (Radha) also casts longing looks in the Captain’s direction.

Captain Tom only has one leg (as did Breen – appropriate casting long before it was a thing) but even so he is a catch, not least because he is the only suitable male for miles around. As the Captain gamely and gallantly plays getting-to-know-you with one young woman after another, outside in the real India life rolls on immutably, like the river that symbolically rolls steadily by.

It’s a Technicolor movie and, because Renoir was shooting it all the way out in India, Technicolor couldn’t be bothered to send one of their technicians to assist and advise on the notoriously tricky process.

This worked immensely in Renoir’s favour. To directors, Technicolor’s technicians were often more a curse than a blessing, going way beyond their brief to dictate colour schemes and lighting designs that suited their process rather than the movie.

Since there was no technician on hand, Renoir did not suffer this problem, but he did have another one. The film he shot was being processed in London, and the turnaround on rushes was ten days (Wikipedia says five weeks, and it might be right. Either way, a long time).

This meant it was impossible for Renoir and his DP, cousin Claude Renoir, to be certain that they had any shot in the can. On the evidence of the finished movie, they compensated by overlighting everything. There is so much artificial light in this movie – shadows ping off in every direction – that it looks like it was shot in the studio. What an irony, considering Renoir’s investment in the authenticity of shooting on the spot.

Powell and Pressburger had made their Indian movie, Black Narcissus, at Pinewood Studios, just to the west of London, four years earlier and from this distance The River looks like Renoir’s attempt to beat Black Narcissus at its own game. Both films are based on Rumer Godden stories. Both contrast stiff colonial types with loose Indians. Both have sex as a disruptor. Both have an indigenous woman caught between two cultures (Radha here; Jean Simmons in Black Narcissus). Both feature Esmond Knight (a Powell and Pressburger regular). And there’s that retina-cleansing bright, bright lighting in both movies – the Technicolor process needs light.

Renoir’s message – sophisticated westerners trumped by simple Indians connected to the deep time of the river – looks hopelessly naive and even condescending these days but was sincerely intended and must have been eye-opening at the time.

The acting is tender and charmingly old-school but it’s only really the white folk who get to do any. The Indians have barely any agency and are ornamental rather than functional. This is most obvious in Radha’s Melanie. Half this and half that, she gets half a storyline and has only half a reason for existing as a character, her Indian mother conveniently dead.

All that to one side, you can’t deny the beauty of the film, a screen-grabber’s treasure trove. The wide multi-hued river, the rich mud walls and beaten earth. Amazingly, it was Renoir’s first colour picture and he loads it up with so many lush shots – every item in the frame sweated over for maximum visual effect – that the only other word that can really describe it is kitsch. This is travelogue film-making – of a time and a place and a system – but of the highest pictorial order. “Beautiful” – damned with faint praise.

The River – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2024