In 2013 a young mother named Fabienne Kabou left her baby on a French beach to be swept away by the tide. Saint Omer is the wistful, powerful, thoughtful and, ultimately, rather sad fictionalisation of the trial that ensued when Kabou ended up in the court on the charge.

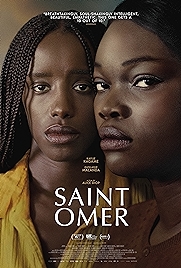

Open and shut, you’d have thought, and possibly that’s what film-maker Alice Diop thought when she first started attending the trial, initially drawn in by the fact that the plaintiff was of Senegalese origin like her. Diop wasn’t there with the intention of making a film about it. Cameras aren’t allowed. But as time went by she realised that this was the subject matter for her next project. A light fictionalisation is the result. Kabou is now called Laurence Coly and is played by Guslagie Malanda. Diop herself is aso part of the story, again lightly fictionalised, as Rama, a novelist played by Kayije Kagame.

What actually plays out in Saint-Omer criminal court is open and shut with a twist – Laurence never denies that she committed the terrible crime but she isn’t sure why she did it. In a strange use of the court’s time she tells the judge presiding over the case that she hopes the trial will help her understand what happened that dark night when she invited the tide to float her daughter away to her death.

The bulk of the film is taken from the trial transcripts. This verbatim material provides much of the film’s power and in any case could anyone have written a character like Laurence? An educated Senegalese woman brought up to be more French than the French, she moved to Paris to study. When that went a bit wrong she moved in with a man called Luc, 57-years-old to her 24. That went a bit wrong too, resulting in a small baby that Luc never wanted, and maybe Laurence never wanted too.

Luc’s defence of his own position is compelling in its own right – the old white guy reluctant to admit that he was a much younger woman as a handy sex buddy rather than a girlfriend or mother of his child. But it’s when the rational runs out of road and Laurence starts talking about a supernatural curse put on her by her jealous aunts that things get really interesting.

Laurence is at the centre of a matrix of ideas about who or what she is. She’s a woman raised in the ways of “the West”, yet she believes that her life has been cursed by dark “African” forces. She’s a student of philosophy who never should have been studying Wittgenstein, says a professor called as a character witness, because Wittgenstein is a white Austrian and Laurence is a black African. But most of all Laurence is a woman, and women don’t kill their kids, they nurture them.

Is Laurence mad? Is she depressed? Is she a conniving creature reaching for African juu-juu whenever it might be useful, as the prosecution suggests? Rama, originally hoping that the trial will give her the source material to write an update on the story of Medea – the murderous matriarch of Greek myth – eventually starts to wonder if there are parallels between her own life and Laurence’s. Female. African. A threeway tug, once The West starts exerting a pull of its own. Why should a black woman be dabbling with white myth etc.

Diop wisely lets the verbatim stuff do its powerful, complexifying work. She lets the two actors do their thing too. Malanda is fabulously good, an ambiguous Laurence to the end. There are suggestions of the monstrous and the mythic here, but Malanda also keeps Laurence’s feet convincingly on the ground. Against her Kagame cannot really compete, but she is also compelling, especially as Rama realises she’s more like the baby-murdering Laurence than she thought.

Diop relies on her background in documentary and her performers, in other words, but little details in the making of the drama have force too – the sporadic use of Caroline Shaw’s a cappella piece Partita for 8 Voices, an avant-medieval choral work suggesting both ancient and modern, is just right. An interesting use of colour – so many shades of brown. And there’s also a drop-in of Maria Callas’s performance as Medea in the Pasolini movie, another forceful, tragic woman (both actor and character) caught in flux. Tellingly, perhaps, it was Callas’s only non-singing role.

This film lasts a whisker over two hours. It flies by, all the while tantalising by suggesting Saint Omer is going to drop into a familiar genre – the courtroom drama – but this is a film that’s more about questions than answers. A courtroom sketch of a peculiar force.

Saint Omer – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2024