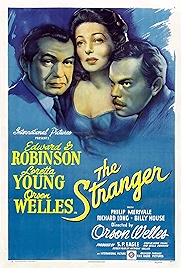

The Stranger is an entertaining enough noirish thriller but the real fun comes from watching it as a contest between a maverick director and a studio that wanted their hireling to turn out Hollywood product rather than a grand auteurish statement.

The director is Orson Welles and the year is 1946. Welles was at a low ebb. He hadn’t been let near a feature film on his own for four years. 1941’s Citizen Kane had flopped and the follow-up, The Magnificent Ambersons, had gone so far over schedule and over budget that the studio had taken it off Welles, cut an hour and reshot whole chunks of it. It also bombed.

Future generations might think of Welles as a genius, but Hollywood at the time treated him as a bumptious pest. So here he is, chastened and behaving himself, being kept on a tight leash by producer Sam Spiegel as he knocks out a regular-folks movie, having signed a contract that gave Spiegel the last word in the event of any artistic differences of opinion. Spiegel also installed Ernest Nims as editor, whose job was to remove Welles’s signature flourishes.

Welles countered by shooting as much of the film as possible in continuous, uneditable long takes. Nims, undeterred, still hacked away, and you can see the results of it in the opening sequence, where a husband and wife are introduced. It looks like they’re going to be a substantial part of the film. They arrive. They speak. They disappear, bizarrely never to be seen again, the result of Nims having removed what was 16 pages of screenplay from the beginning of the film.

The woman, incidentally, ended up being killed by wild dogs in the original treatment, which might not seem to have much relevance to what follows, but it set a tone, and in The Stranger mood was meant to be everything. As Welles observed, Nims “believed that nothing should be in a movie that did not advance the story. And since most of the good stuff in my movies doesn’t advance the story at all, you can imagine what a nemesis he was to me.”

Welles’s 16 pages of (deleted) mood-setting out of the way, he opens his story proper with an establishing shot of the door of a US war crimes agency taken from a very low vantage point, and then follows up with another establishing shot, this time from very high up, of the story’s hero, Edward G Robinson’s investigator Mr Wilson, a mild-mannered penpushing kind of Mr Average, the sort of gradualist implacable nemesis Robinson had perfected in 1944’s Double Indemnity. It could almost be the same person.

Off the story hurtles. Wilson’s plan is to release a known Nazi and follow him as he flees across America. He does so and the trail leads to a picket-fence small town – perfect in its cuteness – where it’s soon established that Professor Charles Rankin (Welles) is a particularly nasty Nazi in hiding, and one about to embed himself even further in US society by marrying Mary Longstreet (Loretta Young), the daughter of a liberal judge and a pillar of society.

The rest of the film, again in a manner reminiscent of Double Indemnity, consists of the patient Mr Wilson flushing out Rankin, who Wilson suspects almost from the off.

The long takes make it an elegant journey, and the cinematography of Russell Metty means it’s a good looking one. Metty had worked (though not as DP) on Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons and would later be Welles’s DP on Touch of Evil. He’s no slouch here – high key lighting for exteriors, high contrast for interiors – though his deep focus imagery isn’t quite up there with that of Greg Tolond (who’d done Kane).

Even so, Welles hated The Stranger more than any of his other films, partly because he was ashamed at having sold out, and also, surely, because Nims’s incessant snipping (he excised another 16 pages through the rest of the film) left Welles’s acting looking foolish. Welles was after something that was overall sinister and gothic, and acted accordingly – rolling his eyes and twirling the metaphorical baddie moustache – but without the mood-setting, the result resembles something much more like a confused smalltown murder mystery. Critics at the time found it a poor second best to Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt, which the truncated version does resemble.

Nightmares still haunt the edges. Checkers-playing drugstore owner Mr Potter (Billy House), who spiderlike never stirs from behind his cash register, gets far more screen time than his character should, igniting speculation as to what Welles really had planned for him (Potter is almost entirely his creation). Prof Rankin is obsessed with clocks and almost at one point launches into a variation on Welles’s speech on cuckoo clocks as Harry Lime in The Third Man. When we learn of Rankin’s precise contribution to Nazism, it makes more sense, but even so, Nims has robbed this metaphor of much of its power.

Loretta Young is singing from the same hymn sheet as Welles – histrionic, almost silent-movie-esque – leaving Edward G Robinson to walk away with the honours as the utterly watchable Mr Wilson.

Though made in 1946 it’s obviously part of the project of wrapping America up in the affairs of Europe – look! even in this small town Nazis lurk! Welles’s inclusion of footage from the death camps emphasises the stakes but also works like a doomed attempt to add bottom to something that’s largely operating at the light entertainment end of the spectrum. Again thanks to Nims.

But. It was a hit. The only film of Welles’s to make proper money when it was first released. Maybe that’s really why he hated it so much.

The Stranger – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022