The Tin Drum won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film in 1980, as well as the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1979. Not everyone was enamoured, though. While the Los Angeles Times thought it “a masterwork of cinema” and the New York Times slightly less effusively reported that it “compels attention,” Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times took against it, doling out only two (out of four stars) in a review that expressed bafflement at other critics’ admiration of the film.

The years have tended to vindicate Ebert. The movie, like the original Günter Grass book on which it was based, has been steadily rerated downwards over the decades, not least since Grass’s revelation in 2006 that he’d been a member of the Waffen SS during the Second World War. Not a good look in a left-wing writer, though to be fair to Grass he was only 17 when he was conscripted in 1944 and had, according to his own account, no idea which bit of the army he was heading towards when he was drafted.

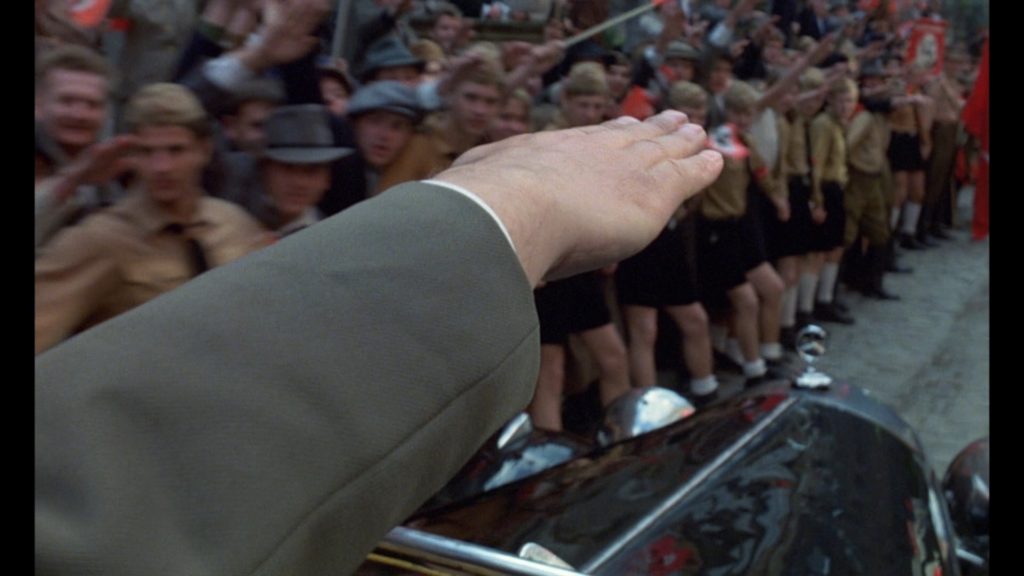

The book is divided into three sub “books” but the movie only takes us as far as the end of the second, and the end of the war. Up till then, in Bildungsroman fashion, it’s followed the life of Oskar, its hero and narrator, from conception up to adulthood, the rise of the Nazis paralleling his own development (or lack thereof). Grass’s plot novelty is that the unnaturally smart Oskar at the age of three comes to the conclusion that this world is no good and so decides not to grow any more. And that’s that. He remains childlike while the world around him changes.

It’s this allegorical aspect of the film that bothered Ebert, and his objection is fair enough. If Oskar is meant to stand for something, what is it exactly? What also bothered Ebert was the titular drum, which Oskar falls in love with at a young age and takes with him wherever he goes, banging it dementedly while letting out a scream that can break glass. The drumming and the screaming are both incredibly irritating, and they are meant to be. Oskar is also meant to be a disturbing presence. If you’re looking for kids who can outcreep Damien in The Omen, here is your candidate.

David Bennent is a gift to director Völker Schlöndorff, a puckish kid who did indeed have a growth impairment and so is quite undersized for an 11-year-old. But Bennent is more than just a lack of height. This is a properly great performance – Bennent catches the demeanour of someone who is older than he looks, the way Oskar walks, the way he turns his head, more stiffly than a child would. There’s something of the changeling about Oskar, the homunculus, and Bennent gets it just right. Oskar is frightening.

In a way this is a magical-realist update of the old German myth of Till Euelenspiegel, the impish trickster who paraded through medieval Germany calling attention to hypocrisy, though in this Germany-gone-mad era, this latterday Till is confined to screaming and staring and sharing his internal misgivings only with the audience.

Hugely in the film’s favour is the mad series of grotesque scenes that Schlöndorff gets onto the screen, whether it’s Oskar’s conception – a soldier crawls under his mother’s voluminous skirts while she’s out in the fields and has his way with her. Or the scene where boys boil frogs to death. Or when a horse’s head is dragged from the sea alive with eels. Or Oskar’s mother eating herself to death on fish. Or Oskar starting a sexual relationship with a young woman who’s also his father’s lover (it’s this stuff that got the film into trouble in Oklahoma and Ontario).

A brightly lit and incredibly good looking movie, it sits in a European tradition somewhere between Fassbinder, angry about the way post-War Germany wasn’t facing up to its Nazi past, and Herzog, who in films like The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser and Stroszek also used fairytale naivety as a way of interrogating current values.

It’s full of lovely performances too. Mario Adorf as Oskar’s father, so stupid he can’t see he’s being cuckolded by his wife’s cousin. Angela Winkler and Daniel Olbrychski as the lovers in question. Charles Aznavour (dubbed out of French into German) as the Jewish toyshop owner who gives Oskar his drum. And Katharina Thalbach as the cousin (depending on which of the two men is Oskar’s real father) who ends up introducing Oskar to the world of sex.

Personally, I’m with Ebert. “The movie juxtaposes Oskar’s one-man protest with the horror of World War II. But I am not sure what the juxtaposition means,” he said. But that doesn’t mean The Tin Drum is not worth watching. Far from it. It’s a big, mad and disturbing affair, and if it’s failed to find a way to get Grass satisfyingly onto the screen, it’s not suffering from a lack of ambition.

If you’re going to make the effort, go for Criterion’s restored version, which adds about 20 minutes to the original version, just how Schlöndorff originally conceived it. Would Ebert like this version any better?

The Tin Drum – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022