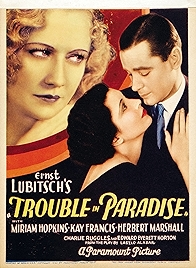

Trouble in Paradise was Ernst Lubitsch’s favourite of his own films. It’s 83 quick minutes of screwball farce, made in 1932 just as Hollywood was putting its own house in order (before the government stepped in and did it), one of the highlights of the pre-Code era. It’s more sexually risqué than later films, for sure, though that isn’t what got it into trouble when Paramount tried and failed to re-issue it in 1935. Banned for decades, it wasn’t really seen again until the 1960s

It’s the story of a conman called Gaston and a thief called Lily who try to swindle/steal each other but instead fall in love. Realising they’re a crack team, they decide to focus their attentions on a rich perfume heiress, Madame Colet. What got the film into trouble is the fact that the conman and the thief are the stars of the movie – and the Code says crime must not pay. They’re sympathetic characters and we’re encouraged to will them onwards as they try to take down the too-rich, too-entitled Colet. Lubitsch even, shock horror for films of the time, makes explicit reference to the recent stock market meltdown and banking crash of 1929. There’s even a faintly Lenin-esque firebrand Communist in it, briefly, to remind audiences of what’s going on outside.

There’s a realism, in other words, slightly out of keeping with many films of the time. But let’s not get carried away – this is still a frothy Hollywood movie, and Lubitsch makes sure the set design (all Art Deco and very modern), exquisitely tailored clothes and high-tone locations lend it an aspirational air. Though Lubitsch being Lubitsch, when the action opens in Venice, the first thing we see is a gondolier collecting trash and dumping it in his boat.

The meet-cute really is cute. Lily pickpockets Gaston’s wallet. He steals her jewellery. She nicks his watch. He nabs her garter. They’re in awe of each other’s skills, though each believes he/she is better at thievery. It’s love. Or is it respect for someone who doesn’t fall prey so easily to trickery?

Later, when Gaston (now posing as Monsieur La Valle and working as the secretary to Mme Colet) starts to fall for her – potentially blowing a hole in the Gaston/Lily plan – a similar psychological dynamic is in play. Gaston might really be falling in love with Mme Colet, or he might have fallen for someone who isn’t taken in by him. If Lily has the animal cunning, Mme Colet has money – and people with money lack the desperation that makes people fall for a conman’s shtick.

The meet-cute is pure Lubitsch – a whole universe done in a thumbnail. And later there’s an even better one, when Gaston and Mme C are wondering if there’s more in play here than an employee/boss relationship. Lubitsch does the whole scene with his camera fixed on a clock, an entire evening’s worth of romantic development done in about a minute with one static shot – though the time keeps jumping forward – and two voices over the top.

A lot of credit has to go to Samson Raphaelson’s clever screenplay, the fourth of ten films he’d write for Lubitsch. And also the playing of Herbert Marshall as the too-suave, too-plausible but always slightly reptilian Gaston. Marshall would become a jowly tin of beef later in life but here, aged around 40, is sleek enough and light enough on his feet to be a plausible romantic farceur (not bad for a man with a prosthetic leg).

Playing Lily is Miriam Hopkins, also just right as the slighty brassy, too-worldly grifter. And Kay Francis is the witty, not-as-dumb-as-the-money-suggests Mme Colet, a dab hand with Samuelson’s repartee – is this the film where the line “Shut up – kiss me” was first uttered? Must be pretty close to the first. Either way Francis is as good at drill-sergeant romance as she is at languid drollery. “That’s the trouble with mothers,” she says to Lily at one point, who is trying to bullshit her with some story about her mother having died. “First you get to like them and then they die.”

Not a line you’re likely to hear an any other film, of this or any other era. Give Trouble in Paradise a go. It’s good.

Trouble in Paradise – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate