Unclenching the Fists could so easily be poverty porn but manages not to be, thanks to an ending offering a sliver of salvation, and a look that’s deliberately trying to avoid the charge that this is just another in a very long series of films using poor people to tell the same story over and over again – it’s tough at the bottom.

We’re in Ossetia, one of those regions that were all but subsumed by the old USSR but seem to be having a revival in the post-Communist era. Even so, it’s a poor place, and the town where Kira Kovalenko’s film is set sits in a ravine where it’s hemmed in on all sides by forbidding sheer slopes. A metaphor for the life of the film’s heroine, Ada, first glimpsed being hit on by a hopeful/desperate teenage boy, and then heading home to be dressed down by her father. “Who put that smell on you?” he asks, referring to the perfume she’s wearing.

At night Ada’s teenage brother Dakko climbs into bed with her. He’s having another of his nightmares, he says, though it all seems inappropriately close. By day Ada works at a local shop selling sweets. She’s taken there by her father who then picks her up after her day is done.

Meanwhile, around her, life in the town goes on. The buildings are mostly Soviet-era blocks. The locals spend their time razzing their cars in symbolic circles in the dust for fun. It could go on like this for ever, Ada bridling at the strict regime she’s living under, working, then going home, where her father locks the entire family in each evening. He’s the only one with a key.

Two things break the cycle. First Ada and Dakko’s older brother Akim comes home. Akim clearly had fled the coop because he was unwilling to put up with his father’s bullshit any longer. Now he’s back and wants to help Ada in turn get away. But dad doesn’t just have the front door under lock and key, he’s got Ada’s passport squirreled away somewhere too.

If this sounds like the set-up for a tale of abuse, it’s more complicated than that. This is a family of intense connection. The father clearly loves the daughter, though maybe it, too, shades into inappropriateness. We’re never sure. Ada also has intense feelings for her brother Akim, and paws him the way her other brother Dakko paws her, the way lovers do, almost.

The second thing that breaks the cycle is a seizure by dad, a stroke, perhaps, which renders him mute and almost immobile. Here is Ada’s moment, but will she take it now that her father needs her more than ever?

What’s made this family so odd, and the father so controlling, is hinted at rather than overtly stated. There are also scars on Ada’s stomach as the result of some accident back in the past. This is the story of a bad thing happening and then a wrong turn being taken, of a necessity somehow having been mistranslated into a virtue. “Choices are a good thing,” one of dad’s friends says at a homecoming party for Akim, “But you always want to come home.” As if there were no question about it, to this town offering nothing in the way of prospects for the lively and enquiring young adult.

Kovalenko shoots it all almost in a documentary style – long takes, little in the way of editing, no music, a real documentary immediacy – and the actors all speak like real people do, sometimes swallowing half of their words, though this is really a drama where pregnant pauses convey a lot more meaning than the conversations.

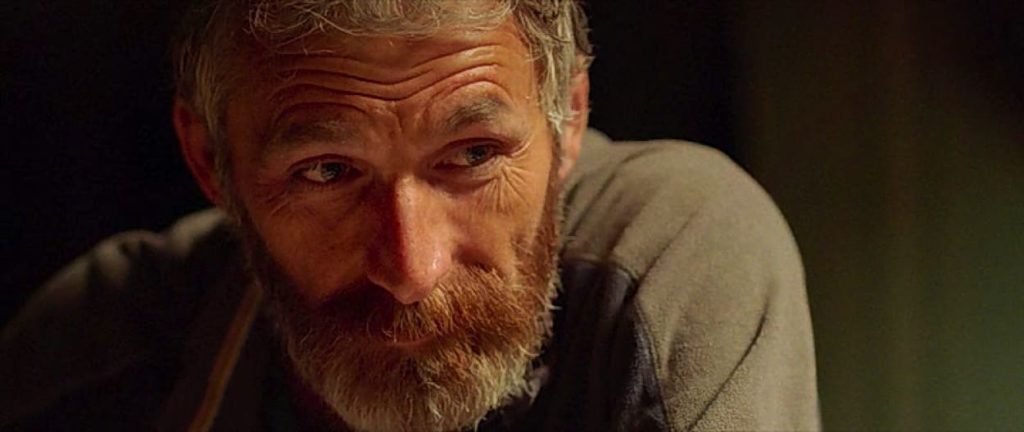

Film-y stuff does happen though. The warm, warm filtration casts a rosy glow over this dusty nowhere – Kovalenko wants us to know that, for all its faults, Ada loves her home and family. At key moments the camera loses its rational grip and becomes subjectively impressionistic. And the performances are carefully constructed, particularly Alik Karaev’s as the charismatically forbidding father and Milana Aguzarova’s, whose Ada is a fearful, resentful, aspirational enigma with a crooked half smile on her face, whether she’s having a bad time or a good one.

That’s the other thing. Poverty porn usually offers no release from the parade of woe. Ada does get moments of joy, and they light up a film which initially looks like it has no intention of going there. Like this family’s odd relationships, Unclenching the Fists is more subtle and layered than it looks.

Unclenching the Fists – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2021