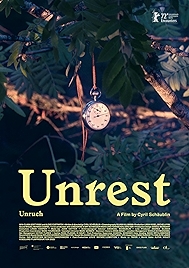

There was a real-life person called Pyotr Kropotkin, he isn’t a fantasy creation of writer/director Cyril Schäublin, who is also excavating his own family’s connection to the Swiss watch industry in Unrest (Unrueh), a film as quiet and precise as a high-end timepiece.

Schäublin’s film follows the bearded Russian political radical (played here by Alexei Evstratov) as he arrives in a Swiss valley, where, he’s apparently heard, the workers are beginning to organise themselves in a loose anarcho-syndicalist fashion.

There, posing as a cartographer making a map, Kropotkin stands back and observes, taking in the working relations of the late 19th century – feudal more than anything. He notices how the workers mutually aid each other – whether it’s sending money off to striking fellow workers on strike for better conditions in America, or simply passing on a box of matches to someone who needs it, even if that someone is the factory boss – and comes to the conclusion that anarchism not socialism is the way forward for the class struggle. Though in all honesty, the activity we see on screen – workers of the world uniting one way or another – doesn’t look a long way away from Karl Marx.

This is the film of Kropotkin’s observations and interactions, give or take, though there’s an autobiographical element too. Schäublin’s own forebears worked in the watch factories fitting “unrest” wheels into chronometers. Schäublin is shooting in the St-Imier valley, where, history tells us, the Anarchist International of St. Imier was founded in 1872. Under the guiding mind of Mikhail Bakunin, it offered an alternative “worker power” template to the one offered by Marx.

So there is authenticity here, and a documentary impulse, something Schäublin reinforces with a strange shooting style that situates his characters in the thick of the melee. It’s about the many not the few. Close-ups are rare. The camera is pulled back and whoever is speaking is often off to one side, hard to pick out, while around them the mass of humanity just goes about its business.

Feet are regularly cut off, and while the framing is deliberate, it’s unusual, as is Silvan Hillman’s cinematography – flat and icily cool (I see that Hillman went on to be the DP on Zimmerwald, a thematically not dissimilar documentary about a forgotten conference in Switzerland attended by Lenin and Trotsky).

For all the Marx, Bakunin, anarchism and socialism, the presiding spirit in Schäublin’s film appears to be the 20th-century theorist Michel Foucault. He’s never mentioned but the fanatical attention to time-keeping, measurement and regulation that Kropotkin observes everywhere in the town has a distinctly Foucauldian flavour.

Almost everyone in this movie is involved in some form of control – whether it’s the local gendarmes, the factory overseers or the innkeepers denying a man a drink because he hasn’t paid his taxes. Everyone works for the Man, though some are more aware of this fact than others.

As Kropotkin arrives in the small town, it is adhering to four different versions of mean time – factory time, church time, local time and municipal time – but he’s turned up at precisely the moment when that world is about to end. In one rare close-up, Schäublin focuses on the telegraph key in the post office, the piece of tech that is going to consign all these different ways of measuring time to history.

Schäublin isn’t out to preach to the non-converted here. This is a fascinating film set in a disappeared world and concerned with a largely forgotten moment and a largely forgotten politics. It’s beautifully made, with much of the acting done by non-professionals, who are remarkably good.

It’s also a coolly analytical one – that is partly its point, after all – running almost as if by clockwork. But there is a slight love story buried in here too. Kropotkin’s attention is caught by one of the young women who fit the unrest wheels and he is taken by her attractive features and her spirit.

There’s not much of the developing relationship between Kropotkin and Josephine (Clara Gostynski), but when Schäublin arrives at the moment when it’s time for Kropotkin and Josephine to express the feelings they have for each other, he writes and shoots the scene with such skill, ingenuity and charm that you wish he’d given us a few more.

Unrest (Unrueh) – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2024