A stark, bare-bones title for a documentary about a stark, bare-bones band, The Velvet Underground sees superfan director Todd Haynes using his own celebrity to gain access to talking heads who might not otherwise talk – the film’s coups are having a warm, chatty John Cale and a voluble and twinkly Moe Tucker on board to deliver the “I was there” bona fides from founder members.

The Velvet Underground are the template for every art-rock or avant-garde rock band ever since. In their jangling, discordant, off-key, unschooled way they burned bright and short, and the cliché runs that though not many people ever saw them, everyone who did so formed their own band.

Todd Haynes doesn’t trot out that myth, but in most other respects this pilgrimage stops at the recognised waystations. To wit: the key movers are Lou Reed (the nice tunes) and John Cale (the arthouse drones). The key album is the first one – The Velvet Underground and Nico – with everything else in its wake. German model/chanteuse Nico was also key, even though no one in the band really wanted her there. They dressed in black. They were awkward. They were a product of Andy Warhol’s Factory. They liked drugs. They hated hippies (When they went to hippie-hangout the Filmore West in Los Angeles to play alongside Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention, the promoter Bill Graham bustled up to them before they went on and said to drummer Moe Tucker, “I hope you fuckers bomb.”).

Haynes spends most of the time on Lou and John, since that’s where most of the creative juice came from. Lou, the sexually confused product of the white picket archetypal 1950s American family who wound up knocking out tunes for low-budget record label Pickwick Records but with a love of Ginsberg, Rimbaud, Hubert Selby Jr and a high regard for Delmore Schwartz’s powerfully direct poetry; John a refugee from an austere Welsh upbringing with a love of John Cage and an education in the avant garde which he brought to bear on the music that he and Reed eventually made.

Cale and Reed start making music together as The Primitives and have a surprise hit with a one-note pop song called The Ostrich. As the band morphs into the Velvet Undergroud, enter Sterling Morrison, a guitarist who can actually play, plus Maureen Tucker, the drummer sister of a friend of Sterling’s, to hold down the band when it noodled off into “nowhereland” (as she describes it) and the band is complete.

But enter, most conspicuously, Andy Warhol, the hero of this story, the one who brings the Velvet Underground into the Factory (it “was all about work,” says Cale approvingly. “It was all commerce.”), who forces Nico on them, against Reed’s wishes, brings in socialites like Jackie O, Rudolf Nureyev and Walter Cronkite to be their audience, provides the light show, “produces” their record – his technical contribution is moot – and takes them out on tour.

There is no actual footage of them playing together live all those years ago, but Haynes negotiates that bump by collaging together so much footage of the times. Like an Adam Curtis documentary, this is a phenomenally well researched film. The archives have been trawled, but more importantly than that, the trawlings have then been sensitively and expertly edited (by Affonso Gonçalves and Adam Kurnitz) to deliver a real feel for the times and the glamorous whirl of life in Warhol’s orbit.

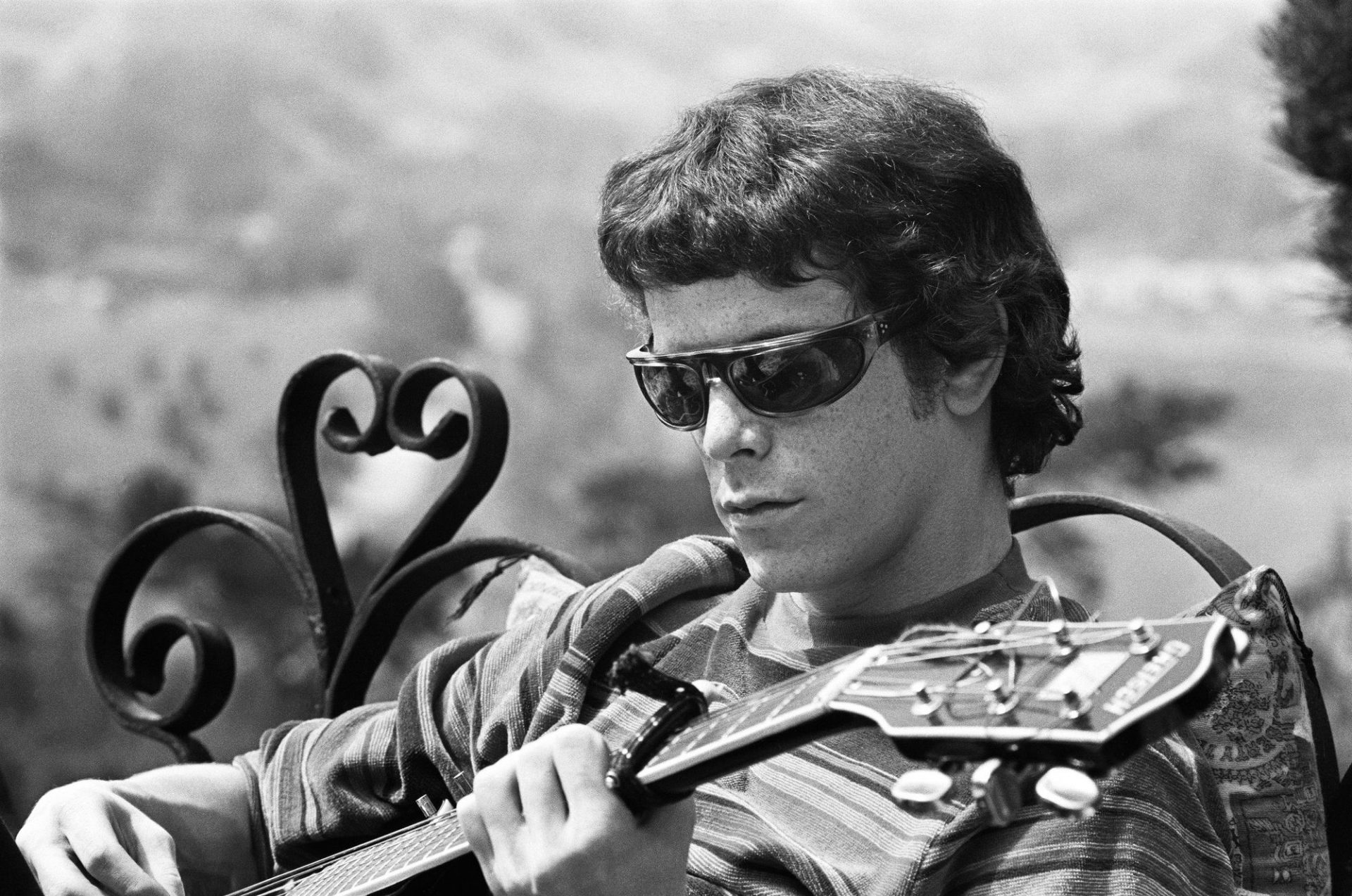

A gift for Haynes and his team is that there is a lot of footage shot by Warhol himself, and his penchant for prolonged black and white 16mm sequences featuring sitters holding what are essentially photographic poses mean that we have the band and many of the other Factory alumni to gaze on as the story unfolds.

Haynes takes an hour to do background of Reed and Cale and the 1960s New York City scene before getting the band together. They rehearsed “the banana record,” as Cale calls it, for about a year before going out on the road. By the time they come back to make their second album, White Light, White Heat, the gilt is off the gingerbread. Nico is gone. The notoriously prickly and jealous Reed fires Andy Warhol and organises the exit of Cale from the band. Sterling Morrison leaves and then finally Lou Reed leaves the band too, leaving Doug Yule (the replacement for Morrison) carrying on. He’d release an album using the VU name, over which calamity Haynes draws a discreet veil.

It’s fascinating that the albums no one really ever talks about when the Velvet Underground are being discussed are the ones Haynes also does not discuss. That his view of Reed (gifted, difficult) and Cale (the avant garde one) are the absolutely trad ones. The role of Nico – can’t sing, beautiful but somehow hauntedly vital. Moe Tucker – an exuberant, ramshackle talisman. And Morrison – the musician.

It’s a very traditional documentary, both in its assemblage – talking heads and clips – and in its lack of revisionism. No bad thing. This is a great story well told. Cale, tanned and healthy, gives it a philosophical bottom and is generous and informative and not at all self-serving. Tucker crackles away and is more likely to speak off the cuff – of Nico: “She simply could not hold pitch.” Of the hippies: “We hated that shit”. She’s the fun element.

And after it all, having charted the rise and demise of what must be the most cult of cult bands, out Haynes the fanboy goes, on the doom-laden All Tomorrow’s Parties, sung by Nico. The first album again. That’s the one – the “banana one”.

The Velvet Underground – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022