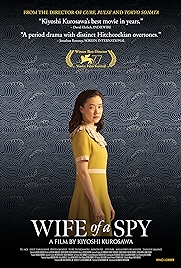

There’s a real lack of urgency in many of the films of Kiyoshi Kurosawa. Sometimes it works in his favour, sometimes against. Against, I’m feeling, with Wife of a Spy. Though there are plot bombs dropped towards the end, and fascinating ideas bubbling away in there to, this high-tone mix of lush period drama and fine acting is undercut by Kurosawa’s tendency to soft-pedal.

Spies, a time of national emergency, marital infidelity, Wife of a Spy doesn’t lack for hot subject matter and, for the non-native viewer, it also offers a window on a world we don’t often see – Japan during the Second World War, when patriotism took on an almost mystical quality, as happens when your emperor is considered a deity.

Which makes the Fukuharas suspicious. He’s in import/export and travels abroad a lot; she lives back at the family home, which is decorated in high European style, all sofas and dark wood rather than tatame matting and low tables. He dresses like an American and so does she, but it’s Yusaku (Issey Takahashi) who’s the driver here, a man of the world, a charmer, possibly a bit of a womaniser, whereas Satoko (Yû Aoi) is naive, sweet, the wife loyal not just to her man but to her country. Can the same be said about him? Is he a spy?

Whether he is or not, she lives in blithe ignorance of exactly what her husband gets up to until she’s given some information about his recent trip to China by an old school friend and longtime admirer Yasuharu (Masahiro Higashide), a fanatical patriot and military investigator only too happy to suggest to Satoko that her husband’s been playing away with a mysterious beauty.

Declarations of honourable intent and fealty to grand ideas tend to come loaded with self-interest in Wife of a Spy, on all sides – if Yasuharu’s stated intention was to alert a fellow patriot to a possible snake in their midst, he also wants to get in Satoko’s pants. Yusaku’s motives are also murky, and keeping international channels of trade open might figure as much in his logic as his stated credo that he’s loyal too, to metropolitan ideals of universal truth and justice.

She – local and patriotic. He – global and not. It gives the film some modern currency, since it’s the political agenda being pushed in every denouncement of “globalisation” and rhetorical flourish of the populists. But there’s also a concern for the role of women. As Satoko starts to take seriously the notion that she might be the wife of a spy she starts to see herself in a new (and not necessarily feminist) light. It makes her a somebody, doesn’t it?

This is Satoko’s tragic flaw. And it’s worth keeping in the front of the mind that it’s the Wife, not the Spy, that this film is about.

There’s usually a decorousness to Kurosawa’s film-making and there’s plenty of it here – beautifully appointed sets, all a bit too box-fresh to be plausible, the slightly sepia look that’s a shorthand for ye olden times in period drama, and a touch of milkiness in the picture, ditto. It’s a film that gives with one hand only to take with the other. The acting is excellently urgent; it’s the storytelling that’s not.

It must be deliberate, surely. Running a “hot” genre with a cool hand can yield spectacular results, as David Lowery proves in A Ghost Story and The Green Knight. Kurosawa (no relation to Akira, and how sick Kiyoshi-san must be sick of saying so) often does the same. There’s fanatical militarism, torture and death in this film, and a curveball plot reveal towards the end. Wife of a Spy barely connects emotionally with any of it. If there’s something else it’s trying to connect to, I must have missed it.

Wife of a Spy – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2021