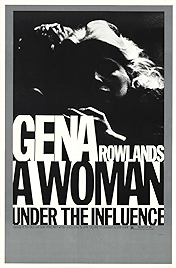

Peter Falk had been appearing in the Columbo series on TV already for about three years when A Woman under the Influence came out in 1974. It’s a film no one wanted to make, and as well as co-starring, Falk helped finance it, with $500,000 he gave (lent?) to his friend, the maverick indie film-maker John Cassavetes.

Once it was made no one wanted to show it either, and Cassavetes was literally walking from distributor to distributor with cans of film under his arm trying to get his new movie screened. And then Martin Scorsese, hot from Mean Streets, stepped in and… the rest is history. Woman ended up with a couple of Oscar nominations, as well as countless other awards. It’s often cited as Cassavetes’s best film.

It’s the story of a wife and mother, Mabel (Gena Rowlands, Cassavetes’s wife), a loose cannon mentally, and her journey into and out of the “nuthouse”. Mabel is married to hot-headed working-class-guy Nick (Falk), she has three lovely kids, plus her mother (played by Rowlands’s own mother, Lady Rowlands) and her husband’s mother (Cassavetes’s mother, Katherine Cassavetes) around her, plus various other adults – the kids’ friends’ parents, her husband’s workmates. What she doesn’t have is a space or life of her own.

For all Falk’s pains getting the film made, he got boos from some feminist audiences when the film was first screened. His name comes up first in the credits. “Starring Peter Falk”. When it’s undeniably Rowlands’s film.

But there’s a logic in putting Falk’s name first. What, after all, is Mabel under the influence of?

As we first meet her, expecting Nick home for a date night only to learn he can’t make it, it looks like it’s booze that’s Mabel’s master. She necks a few drinks, heads off to a bar and, more drinks consumed, picks up some random guy for easy sex.

The ideas of the “anti-psychiatrist” RD Laing were in the ascendant when Women under the Influence was made. His notion (apologies if I’m distilling it to the point of absurdity) is that insanity is an entirely sane response to an insane situation. By this theory, and it seems to be one that Cassavetes is embracing, Mabel isn’t mad, she’s been driven mad, by her husband, her extended family, the demands made on her, the patriarchy, call it what you like. She has no time to be herself and so some part of her has decided to be someone else.

Not everyone likes Rowlands’s performance. Too florid, melodramatic. She’s the classic woman on the verge of a schizophrenic episode, humming, saying random nonsenses, bursting into song, playing the coquette, then the woman scorned, a mass of verbal and gestural tics. But that’s Mabel, not Rowlands we’re watching, surely. Maybe it’s not coherent, but then this sort of schizophrenic behaviour isn’t coherent, that’s why we call it mad. But, again, that’s the character not the actress. The fact that criticism of Rowlands’s performance so often confuses actor and character says all you need to know about the performance.

In an early scene Nick brings his engineer colleagues back from pulling an unexpected all-nighter and Mabel cooks them all spaghetti. Watching Mabel among all these men is fascinating. Some bit of her personality she knows exactly how to deploy – she flirts with most of the guys – it’s the other bits, her married self, her motherly self, that don’t work so well. When she’s asked to deploy those, a fuse blows. It’s discomfiting.

The hothouse atmosphere leading to impending collapse is emphasised by Cassavetes’s use of the mothers – his makes a brilliantly severe matriarch, hers is much warmer and supportive. Both, following Laing, are way too involved in this family’s business. Casting real mothers makes that point brilliantly (it’s also cheap).

Is Cassavetes making a pitch for the nuclear as opposed to the extended family? If so, this a far less radical film than is often suggested – the nuclear family is largely the creation of the post-war nuclear era, the 1950s, after all.

At the time the shooting style was, however, radical, the handheld camera and shallow focus giving the whole thing a documentary-like realism. This is a film-maker telling it like it is, the camera suggests. There are comparisons with Ken Loach’s TV docudrama Cathy Come Home, most apparent in the extended sequence where the doctor arrives and Mabel is (eventually) forcibly injected with a sedative so she can be taken off to the asylum. Harrowing stuff, and reminiscent of the scenes when Cathy was separated from her children.

Both Loach and Cassavetes were heavily influenced by the French New Wave, its insistence on “real life” and marginal characters, but though Cassavetes also borrows the New Wave’s jump-edits here and there, he’s aiming for more documentary veracity than the New Wavers – hence his characters’ tendency to ramble, and his reluctance to get out of a scene early enough.

For all its many splendours, A Woman under the Influence is simply too long, and at 155 minutes this important film is in many respects its own worst enemy. A bit of old-fashioned dramatic compression and shaping would wouldn’t have hurt at all at the production stage. Maybe someone now should take it and give it a good, hard edit.

A Woman under the Influcene – watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2021