Women Talking could have got a lot of dramatic mileage simply by telling the story of what happened rather than what happened next. But it opts for the latter, a daring ploy that eventually yields results, though there are moments on the journey when it looks like it’s not going to make it.

Here’s what happened. In a devout, modernity-shunning Mennonite community in Bolivia between 2005 and 2008 a number of women and girls started waking up mornings to discover they’d been raped in their sleep. The youngest of the 151 victims was three, the oldest was 65. The community elders suggested that Satan was responsible, or one of his demons or possibly the victims were just being hysterical. But it turned out that the perpetrators were a group of Mennonite men, who were using animal anaesthetic to knock their victims out before having their way with them.

As a result women and girls ended up injured, traumatised, diseased or pregnant. Eventually, after the crimes came to light, eight men ended up receiving lengthy prison sentences for the crimes.

Following the approach of the original novel by Miriam Toews, Sarah Polley’s film largely draws a veil over these events. What might have been a crime or revenge thriller instead focuses on the reaction of the women of the colony, or a small group of them, as they meet to discuss how they should react to this monstrous crime.

As the women talk, three possibilities suggest themselves. Stay in the colony and forgive the men. Stay and fight back, insisting on drastic change in the way things are run – the women are not educated, cannot read and have no say in how things are run. Or leave and re-establish a more female-centred colony somewhere else.

After a vote of all the women in the colony, option one – stay/forgive – is ruled out. Stay and fight and leave are now the two options.

This is what, in 12 Angry Men style, the rest of the film consists of, the women sitting about and hashing it out, arguments flying this way and that while in the background their Christian faith keeps a sheet anchor on the discourse and the larger matter of practicality – how to make your way in a 21st-century world when you are living a life out of the 18th – is largely left to one side.

It looks, for a good chunk of time, as if Toews and Polley are laying out the way that the patriarchy works. Keep women subdued, out of the equation, and you can do with them what you like. It feels, grimly, like a lecture. Feminist propaganda, laid out didactically and programmatically. On top of the hectoring, there is little about women in headscarves talking that’s cinematic. It’s all tell and no show.

But at a certain point that starts to shift, as the debate broadens out – to the essential nature of men, for instance. If it is inherent in them to be brutish, can they help themselves? And what to do with their teenage sons if the women do decide to leave – take them along or leave them behind? More broadly, is their god a merciful one and active in the world? If not, where does that leave the women’s faith, which has obviously catastrophically failed them but is still presented as a pillar of strength, a motivating force and a power for good.

A hierarchy of wisdom starts to assert itself as the older women (played by Judith Ivey and Sheila McCarthy) come to the fore. The girls, meanwhile, (Emily Mitchell, Kate Hallett) stop rolling their eyes and larking about and become part of the conversation too.

Bit by bit, it becomes claustrophobically engaging.

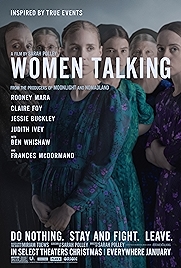

Frances McDormand’s name is prominent in the advertising, but it’s there as a lure. She’s an executive producer and is on screen for maybe ten minutes tops.

Instead Jessie Buckley, Claire Foy and Rooney Mara are the axle on which this movie turns, as the three women with the most volatile opinions voicing their doubts as they zigzag towards a decision. Their performances are all excellent, though for my money it’s the subtly charming Mara who comes out on top, as Ona, the now-pregnant victim whose situation perhaps gives her arguments more heft.

Apart from Ben Whishaw there are no men in this story. He plays in effect a secretarial role, tallying up the women’s arguments into a series of plus and minus points and writing them up in large letters to be pinned on the wall. Even large, the women cannot read them.

Director Sarah Polley puts faith in her cast. Her film’s colour palette is so desaturated it’s almost black and white, her camera movements are never showy, while Hildur Guðnadóttir’s largely string- and harp-driven score elegantly supports rather than stridently proclaims. Polley’s faith and those artistic decisions are handsomely repaid in what eventually reveals itself to be a highly unusual take on the prison-break drama.

Women Talking – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2023