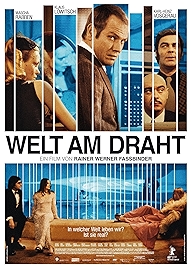

World on a Wire (Welt am Draht) is German auteur Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s only stab at sci-fi. An epic 3.5-hour behemoth, it was originally shown on TV in two parts, and starts as Fassbinder means it to go on, setting up questions about what we’re seeing in front of us.

The opening shot is done on a lens so long it causes an atmospheric shimmer. The picture wobbles just a touch, as if we’re looking through a heat haze. When the people we’re seeing start speaking, their voices have the dead flat ambience of a dubbing studio. So much for atmosphere – we’re disconnected from these businessmen out on the street and entering a building.

Amateur at work? Maybe, but Fassbinder, for all his usual lackadaisacal approach to detail, might already be suggesting that looking and seeing, what we perceive and what’s actually going on, are two different things. This is an adaptation of Daniel Galouye’s novel Simulacron-3, which also went by the title Counterfeit World. The novel was one of the reference points for the Wachowskis when they were sketching out The Matrix.

Playing Fassbinder’s outsider hero is Klaus Löwitsch as the rather meat-and-potatoes Fred Stiller, the new chief technical officer at the Institute for Cybernetics and Futurology whose advanced super-computer has built an entire simulated world populated with 10,000 people so lifelike that the simulations believe they’re real humans.

Stiller’s predecessor met an unfortunate end, exhibiting erratic behaviour before winding up prematurely dead, his fingers on the computers that powered the world he in part created. Stiller is not long in post before he, too, is beginning to behave oddly – asking questions about disappeared colleagues no one else has heard of while complaining the whole time about crippling headaches.

Entering film noir territory, Stiller dons a hat and a weary expression and jumps into a white Corvette to find out what’s going on, like some latterday Philip Marlowe or Mike Hammer, bumping into many a dame on the way, each one of whom finds him ravishingly attractive.

To the 21st-century audience the astonishing reveal at the end of part one won’t come as any surprise at all. We have all guessed long long before Fred has finally had it explained to him, in a duh moment, how exactly he fits into the situation he finds himself in, the reason behind the missing people, why he keeps getting headaches, and also, possibly, why all these mane-haired hotties keep throwing themselves at him. For the few who haven’t twigged – no spoilers.

Matrix fans will enjoy little moments the Wachowskis also seem to have enjoyed – the contraption allowing people from the Institute to enter the simulation, the fact that, once inside the simulation, a telephone is the device used to bring the voyager back.

But this is a more overtly philosophical drama than The Matrix, with an early reference to Zeno’s Paradox – motion is an illusion – and later discussions namechecking Plato and Aristotle. There’s also a conspiratorial political subplot about the government and corporate capitalism being in cahoots, which brackets World on a Wire with other paranoid thrillers of the time, such as The Parallax View, Three Days of the Condor and The Conversation.

Shot on 16mm film and once thought lost, this epic has had a full restoration, by the Rainer Werner Fassbinder Foundation. It was supervised by original DP Michael Ballhaus, and it does justice to the original material. That’s handy because the reason to watch the film isn’t for the thriller element, the deep chat or the fanboy comparisons with a later film, it’s Fassbinder’s lush, lurid, faintly decadent mis-en-scene, pre-figuring David Lynch to some extent, his insanely busy compositions and his highly original camera. He keeps his two DPs (Ulrich Prinz when it’s not Ballhaus) on their toes with a glut of insane zooms, rapid dollies backwards, moments where the camera spins through the room again and again, shots that are off kilter, followed by ones that are rigorously symmetrical.

There are so many mirrors and polished surfaces, so much glass fractalling images of people back at us that it’s surprising we don’t catch sight of Ballhaus or Prinz (I think there’s the foot of one of them somewhere).

It’s a good thing because this, for all the giddy adjectives just used, isn’t a giddy film. In fact it gets a bit leaden in parts and is simply way too long, especially if you’ve worked out what’s afoot before the slowpoke Fred.

If length is really a concern, there is a much shorter, but much less successful, adaptation of Galouye’s original story, which goes by the name of The Thirteenth Floor. It came out in 1999 and was shortlisted for the Saturn Award for Best Science Fiction Film. It lost to The Matrix.

World on a Wire – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022