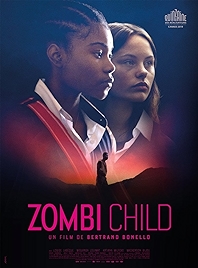

There were zombie movies before George Romero came along and shook the genre up in 1968 with Night of the Living Dead and at first Zombi Child looks like it’s harking back to an older tradition of zombie movie, like 1932’s White Zombie or 1943’s I Walked with a Zombie.

We’re in Haiti in 1962, where an opening shot shows us someone assembling something nasty-looking from various bits of pufferfish innards and other voodoo bits and bobs. The resulting powder is then put into a man’s shoes. The man “dies”, is buried, disinterred and in short order – this all taking about five minutes of screen time – is working on a sugar plantation, an old-school shuffling, grunting zombie.

Is it an allegory of the relative powerlessness of the working man without a union to protect him? Or, more obviously, for slavery? There is barely time for these thoughts to raise themselves before we’re off to Paris, the present-day, at an elite school for girls, where director Bertrand Bonello’s left to right camera pan reveals a lone black face in a class of white ones.

Mélissa is a new arrival, and she listens as attentively as the white girls to a teacher expounding on colonialism and revolution before joining her new classmates, who are unsure about this new arrival from Haiti but think she might be cool enough to join their sorority – girly chats and midnight meetings a speciality.

The action then oscillates between Haiti in 1962 and Paris in the 21st century. Bonello contrasts a hot, humid and dark Haiti echoing to the sound of night creatures with a cool, modern and functional Paris, where the twittering of elite misses fills the air.

In Haiti it turns out that the new zombie isn’t quite as zombified as it seemed, while in Paris the true nature of Mélissa is hinted at – she grunts, she’s “different” – but not quite revealed.

She’s the titular zombie child, I thought. No spoilers, but not really.

The Haiti end of the story is based on a real account written by a man called Clairvius Narcisse (what a great name), who claimed he was a zombie slave between his “death” in 1962 and his eventual escape from a sugar plantation in 1980. In Haiti Bonello is reasonably faithful to the bare bones of Narcisse’s account, while in Paris he continues the exploration of the social habits of women in closed societies which we saw in his 2011’s House of Tolerance (which goes by two other titles: House of Pleasures and L’Appollonide: Souvenirs de la maison close, and is well worth checking out whichever name it’s going by).

If it is an examination of colonialism, slavery and so on, then Bonello is going about it all in a very obtuse way, though as the finishing line comes into view he does at least start to bring the two worlds into closer sync by introducing Mélissa’s aunt (Katiana Milfort, very effective), a “mambo” who is going to perform a voodoo procedure for one of Mélissa’s school chums, the lovelorn Fanny (Louise Labeque).

So, thematically never quite gelling, which is something you can’t say about the acting, which is uniformly great. At the Paris end Wislanda Louimat is the standout, a self-assured presence as Mélissa, while over in Haiti the sense of real life captured is more profound, partly because there are so few words spoken, partly because, I suspect, Bonello is weaving in actual documentary footage at key moments.

Voodoo spirit Baron Samedi turns up as a character in a nicely evoked bit of voodoo ritual towards the end, the first time I think I’ve seen him in a film since Live and Let Die, Roger Moore’s debut as James Bond, and not a helpful mental association. And if you think that’s a slightly leftfield direction to be heading in, Bonello himself is doing it too, ending the film with outro music of Gerry and the Pacemakers singing You’ll Never Walk Alone, the Liverpool FC anthem. Come on you reds!

Zombi Child – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2021