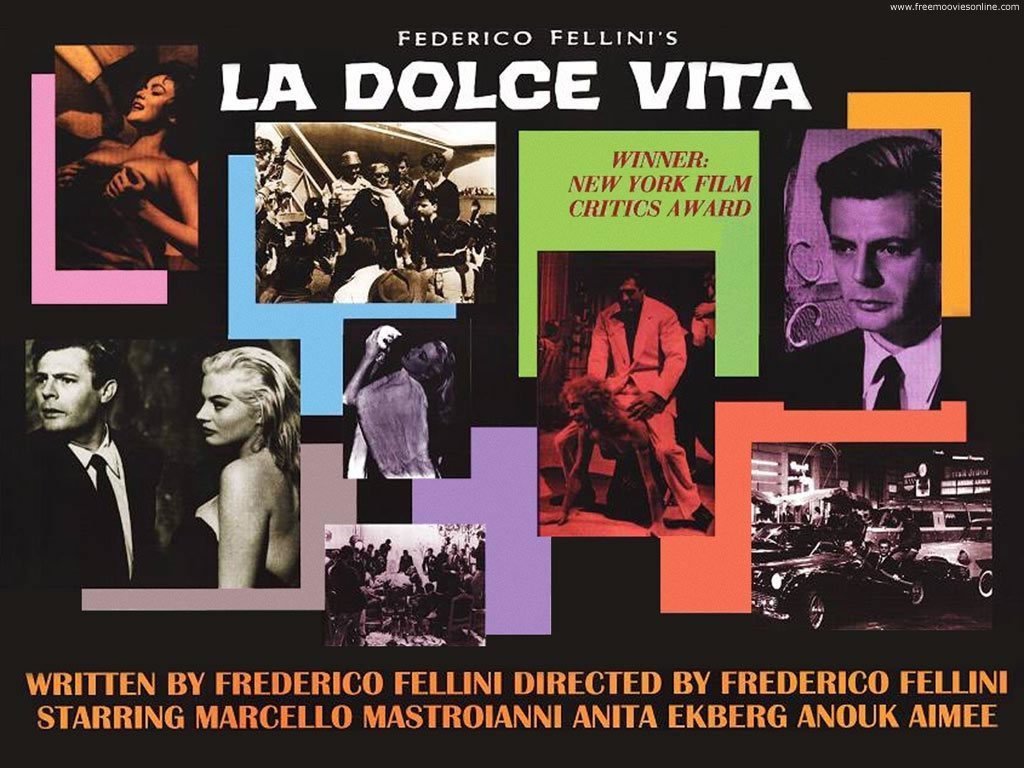

La Dolce Vita might not be the best Italian film ever made. Or the cleverest, steamiest or most gripping. But it is the most iconic. Here’s why…

Just a touch over 50 years ago the assembled critics at the Cannes film festival gave Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita a standing ovation. Not at the end of the film, or even at the moment when Anita Ekberg gets into the Trevi fountain, its most remembered scene. No, what got them to their feet was the film’s opening shot.

It’s of a huge statue of Jesus Christ being airlifted out of Rome, the Eternal City. It doesn’t look like much now but back then this shot came across as a supernatural endorsement, a masterstroke of directorial bravado and a manifesto all rolled into one. What followed was Fellini’s gloriously languid, profoundly seedy exploration of la dolce vita, in English the good or sweet life, an examination of the godless hedonistic lifestyle of late nights, throbbing music and wham-bam relationships.

The critics cheered at the end of the film too, but by then they were less sure of the film’s moral message, particularly in relation to their own occupation. What they had watched was the story of a playboy (Marcello Mastroianni), who instead of pursuing the high calling of being a writer worked as a journalist churning out pieces on film stars, late-night society and what we now call celebrity culture. Over the seven giddy nights and weary dawns that the film follows him Marcello (also the name of his character) stoutly refuses the appeals of his fiancée to stay home with her, instead preferring to spend time in night clubs, prostitutes’ bedrooms and in the company of a visiting actress (Anita Ekberg).

The iconic scene, in which the pneumatic film star has a Lindsay Lohan moment in the fountain, says it all. Here it is, big boy, she seems to be saying, come and get it. Marcello doesn’t get it, in any sense. In fact all he’s got by the end of the film is a terrible sense of self-disgust, an emotion Mastroianni could express better than almost anyone.

At the beginning of the 1960s, with the Beatles and free love just around the corner, this sentiment – that the sweet life perhaps wasn’t all it was cracked up to be – was a real challenge to the zeitgeist. Sure, the film contains the sort of anti-materialist idea that progressive and left-leaning critics of the day wanted to hear. The worrying bit was the moral message that went along with it – don’t be fooled, the film seemed to be saying, this life of ease and luxury, it’s tinsel, not gold. The Catholic Church, meanwhile, saw only the tinsel, the depraved values and the glorious figure of Ms Ekberg and missed the whole point of the film. Immoral, it thundered. As did the Italian government which thought the film “shameful”.

Fellini was a communist (of sorts) and a catholic (also, of sorts) so there was some political and religious underpinning to his anti-materialism. But even so, at that time his film was about as bold a statement as could be made. Italy was ruined by the Second World War and in its aftermath Italians starved to death. To make a film about the perils of excess in a country where people had only recently been reduced to eating grass, the idea that the sweet life was bad when any sort of life was in short supply, it wasn’t just inappropriate it seemed a sick joke.

Fellini was also an Italian, of course. A fact which possibly influenced him more than his religious and political affiliations. Differing from their neighbours the French, whose films return constantly to the theme of personal bourgeois obsession, Italian films love to take an axe to cultural certainties. Whether this is down to the unsettled nature of Italy’s politics, the country’s relative youth (Italy only became a nation in 1861) or because of a butterfly love of changing fashion, who can say? Whatever the reason, the films of Fellini and his peers (Pasolini, Visconti, Antonioni) all challenge the status quo. In La Dolce Vita‘s case this was the let-it-all-hang-out tolerance of 1960s Italy, so new it had barely even solidified.

Did Fellini know at the time that the consensus he was questioning was the one which was to hold sway for so long? La Dolce Vita has aged, for sure, but its story of trash journalism and celebrity culture, the lure of easy sex and busty women, the rejection of high culture in favour of low, that hasn’t dated at all. In fact his film seems more relevant now than it did at the time.

In this context it seems almost too good to be true that La Dolce Vita also gave the English language a word with which we’re all familiar and which sums up the narcissism, superficiality and voyeurism the film is so concerned with. Paparazzi. Fellini bestowed the name Paparazzo on a photographer friend of Marcello who flaps through the film snapping celebrities.

La Dolce Vita is a film with a message but also a film with characters we only need to see for a second to comprehend. Mastroianni, in black shades, passive, a man in crisis, without a centre, searching for meaning in his life. Ekberg, not so much a woman as the embodiment of the desirable female, clad in a black sheath of dress but she might just as well have been standing, Venus-like, on a shell.

Ekberg never played another role to match it. Nor did Mastroianni. Because they weren’t playing mere humans but archetypes representing all of us, or that part of us that’s come home at dawn, all partied out and wondering just what the hell we’re doing with our lives. In short, this is the film for the full-on, siren-wailing existential crisis. And if that doesn’t count as iconic…

La Dolce Vita – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2011