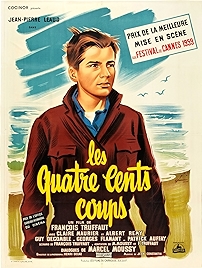

The 400 Blows is a monster classic of the French New Wave with a meaningless title, a literal translation of the original French Les 400 cents coups. “Raising hell” would be a more idiomatic way of putting it and the original US subtitler even suggested Wild Oats. But the distributor preferred to stick with the literal and more enigmatic (in English anyway) translation.

The Wild Oats being sown, the Hell being raised, the 400 Blows being struck are by the central character, Antoine (Jean-Pierre Léaud) modelled on director/writer François Truffaut himself, a kid kicking against the pricks at home, at school, getting into trouble with the law, playing hooky to go to the cinema, realising his parents don’t love him, going wild, stealing, getting caught and ending up in a reform school.

It is in essence a Great Expectations story except here the hero has no mystery benefactor to haul him upwards through society. In reality Truffaut had Cahiers du cinéma founder André Bazin as his Magwitch – spoiler, if you’ve not read the Dickens classic – and the film is dedicated to his mentor’s memory (he’d died, aged just 40, as production was about to start).

Though Agnès Varda might have directed the first New Wave film, The 400 Blows was the breakthrough which established the style as an international force. Truffaut had written the “auteur theory manifesto” in 1954 for Bazin. A Certain Tendency in French Cinema railed against the artificiality evident in post-War French cinematic output and the practice of adapting literary and theatrical works for film. Truffaut argued that cinema was its own artistic beast and that a director didn’t need a dog-eared book as his source since his camera was his pen (the New Wave’s so-called caméra-stylo).

Ironically, the New Wave borrowed much of its unfussy style and focus on everyday people from the theatre, in particular the “kitchen sink” realism of the Angry Young Men who’d shaken up British theatregoers earlier in the decade. Once the French New Wave exploded outwards, it touched everyone from Kurosawa in Japan to Dick Lester in the UK, then crossed the Atlantic to to influence Scorsese, Friedkin, Bogdanovich, Coppola and Spielberg (who cast Truffaut in Close Encounters of the Third Kind as an acknowledgement of the debt).

It helps that it’s an instantly and insistently Parisian film, from its opening shot of the Eiffel Tower and its destination locations – Pigalle, Sacré Coeur, Montparnasse – with a trilling musical soundtrack by Jean Constantin which could only be more Gallic if it featured accordions (it doesn’t). Bold strokes.

Unlike later, more austerely New Wave works – all you need is a girl and a gun and a handheld Bolex kind of thing – The 400 Blows is technically slick, with a carefully used camera, full of artful dolly shots, even in tight spaces, overhead shots, dissolves to indicate the passing of time, perhaps more in hock to the fragrant, well made French cinema Truffaut had vilified than it was letting on.

But its focus is what marks it out as something different – “cinema in the first person singular,” as Truffaut put it. This is the world seen through the eyes of a kid, maybe 13 years old, from his level, with his concerns. We experience what he experiences – a spiteful teacher, his mother kissing a stranger, a moment of escapism in the cinema (twice). It’s a film that’s all about escaping – from school, parents, social structures, “whatever you got” as Marlon Brando had memorably put it in 1953’s The Wild One when asked what he was rebelling against.

Jean-Pierre Léaud is so natural as the naughty Antoine that it almost doesn’t seem like it’s a performance. He’d make another four films as the director’s avatar so clearly Truffaut was impressed too. As for the rest, Claire Maurier as his bottle-blond mother and Albert Rémy as his cuckolded, good natured father manage a canny mix of caricature and idiosyncrasy.

Decades on the film still looks fresh though it’s been so plundered by subsequent directors that its stylistic innovations have all been absorbed into mainstream film language – no one is upset by a shaky camera or a grimy kitchen any more. What still remains, though, is Truffaut’s skill at giving us a film that takes its hero at his own estimation, but also pulls back from time to time to remind us that this is a just a kid.

Which is what that famous final freeze-frame of the face of the wide-eyed young Antoine is all about, after he’s run away yet again and arrived at an unbreachable barrier, the sea. A frightened child who’s run out of road. Where is this story going? Why is there no happy, traditional resolution? Is this a “to be continued” finish? All good questions.

The 400 Blows – Watch/buy the excellent Criterion restoration at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2021