Philosophical (ie moody) sci-fi movie After Yang picks up on Philip K Dick’s sci-fi reflections on the possibility of consciousness in bots. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, and all that. Dick’s stories tends to arrive on screen dark – Blade Runner, Total Recall, A Scanner Darkly, Minority Report – but director Kogonada decides to go one better than any of those with a film that is almost stygian in its gloom.

No matter which way you come at this movie – soundtrack, acting, delivery of speech, clothing, cinematography, framing, screenplay – that doomy, gloomy mood is there. It makes for a meditative experience, if you’re up for something that could also be bracketed with Solaris, another one for lovers of the underlit corner.

As the action opens we meet Jake (Colin Farrell), Kyra (Jodie Turner-Smith), Mika (Malea Emma Tjandrawidjaja) and Yang (Justin H Min), a family set in some indeterminate future where everyone wears natural fibres, there’s barely any plastic, cars drive themselves and communication happens via life-size hologram.

They’re having their photo taken by Yang, who turns out to be a “technosapien”, a bot with smarts, who suddenly, within seconds of the movie kicking off (it’s not a spoiler) stops working, plunging young daughter Mika into despondency. She loved him like a brother.

Technosapiens appear to be contain some organic element, and so as dad Jake drags Yang from repairers official and corporate to backstreet and grungy, a clock is ticking (or whatever they do in the future). Unless he can be repaired quickly, Yang will soon start to decompose.

But before he does so, tech-sceptic and old-school guy Jake (he runs a failing business selling proper tea) discovers that Yang’s “core” contains a memory stick, part of a long abandoned experiment by scientists to see which memories technosapiens might consider important and worth saving. And as Jake starts to review what’s on the stick, the movie reveals what it’s about.

Can people form relationships with bots? Since people will form relationships with stones, the answer is obviously yes. But how about – can bots form relationships with people? Are their relationships based on love or is it transactional? What is love at this level? Does the ability to feel love arrive at the same time as consciousness? Are they the same thing? Can bots ask philosophical questions like these? More importantly, can they be troubled or changed by any conclusions they might come to?

Kogonada gets visual with Yang’s memories. A montage. People. Places. Mika as a baby. A toad hopping. A butterfly. A pretty young woman (Haley Lu Richardson), who will feature later on. Wind chimes. Jake and Kyra sharing a moment of tenderness. It is like an Instagram page specialising in wellness, though these moments could also be nods back towards the pillow shots of the Japanese director Yasujirô Ozu. Which would seem like a fanciful suggestion, except that Kogonada is not this director’s given name – that’s a bit of a mystery. He’s half-borrowed it from Kôgo Noda, Ozu’s regular screenwriter. So maybe?

This is your multi-ethnic family, and though nothing is made of the fact that Jake is white and Kyra is black, much is made of the fact that Mika is ethnically Chinese. Yang was bought (second hand) specifically to give her some connection with her “roots”, even though Yang (in flashback) doesn’t seem to have got much further in his assignment than sharing a few “Chinese Fun Facts”. Quite how much Kogonada (and writer Alexander Weinstein, on whose short story Saying Goodbye to Yang the film is based) are trying to explode the notion of ethnicity-as-identity is unclear, but there’s obviously something absurd about a robot being ethnically “Chinese”, even if it rolled off a production line in the People’s Republic (if that still exists in this indeterminate future).

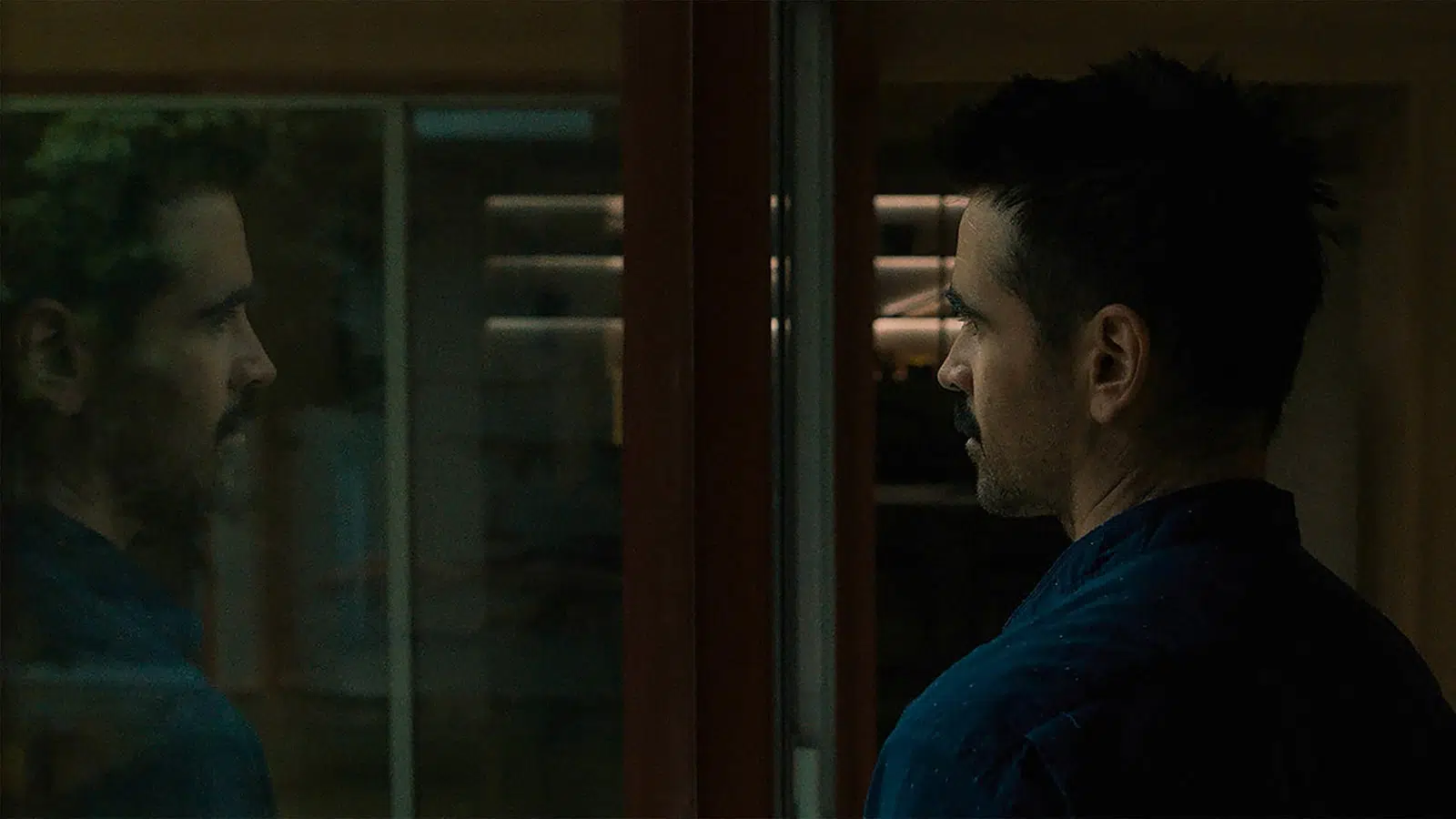

As said, Dark. Dark Dark. Everyone speak sombrely, with pauses between sentences… and words. The soundtrack, by ASKA, operates as if peeping over the back of the sofa – a squeak here, a murmur there. Benjamin Loeb’s mournful cinematography is on some sort of a dare to see how many lights can be turned off. That shot of the family in the garden above is entirely unrepresentative of the film. The shot of Jake (Farrell) up top, that is.

The whole thing lacks urgency but it’s meant to. It floats, in limbo, as Yang does, between life and death, knowingness and nothingness. There are things going on below the surface that never cause a ripple above. After Yang takes sci-fi about as far as it can go down a road of wistful speculation and contemplation.

After Yang – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022