There are two films called Asylum from 1972. One is typical of its era – a compendium horror produced by the Amicus studio, directed by Hammer regular Roy Ward Baker, written by Robert Bloch, of Psycho fame, and starring Peter Cushing. And so is the other, a fly-on-the-wall documentary taking seriously a countercultural moment at full flood.

This is a review of the latter, just to disappoint the lovers of the lurid, a sober look inside a therapeutic community based in a small house in the East End of London, run by Dr RD Laing and his fellows in the Philadelphia Association, where clinicians and patients interacted together in a community in what was meant to be a mutually supportive environment.

Laing’s ideas were probably at their height in 1972. A charismatic psychiatrist strongly associated with the “anti-psychiatry” movement (a tag he rejected), Laing strove to show that “madness” is often a fairly reasonable response to impossible (often family) circumstances. “They fuck you up, your mum and dad./They may not mean to, but they do.” Philip Larkin caught the mood in his 1971 poem This Be the Verse, as Ken Kesey had done in his 1962 sanity-in-the-asylum novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and John Cassavetes would in his 1974 opus A Woman under the Influence, as close to pure RD Laing as you’ll find in feature films.

Laing also wrote poetry, and his 1970 book Knots, full of insightful psychological conundrums, had sold well. He was something of a superstar when director Peter Robinson and his crew turned up at the unassuming house to film “day in the life” footage.

Ha! He’s not there. In fact Laing is barely glimpsed in this film, though his influence pervades this shabby house, the doors painted purple, the tatty wallpaper orange and daubed with slogans. A studenty atmosphere prevails. People eat squatting on the floor. There are no rules, apart from “pay the rent”. If you want to see a therapist in town, you may. If you want to take any number of psychoactive or recreational drugs, that’s fine too, though the non-medical approach is preferred.

It’s a gentle, nurturing place, an “asylum”, Laing explains at one point, in the old sense of the word, a place of refuge where people can gather themselves when they’re feeling “a bit scattered”.

Two things become obvious while watching. The first is that the clinicians are, to an extent kidding themselves if they think that the divisions between doctor and patient have been dissolved. Laing acknowledges this right up front as the film begins, in some remarks about unequal power relations in hospitals, where no matter how matey your therapist is, he/she still has the key to your cell. However, the fiction seems to work (mostly). Which brings us to the second point. How should a clinician react when this relentless “nudging” (to borrow a later notion) of human behaviour doesn’t work?

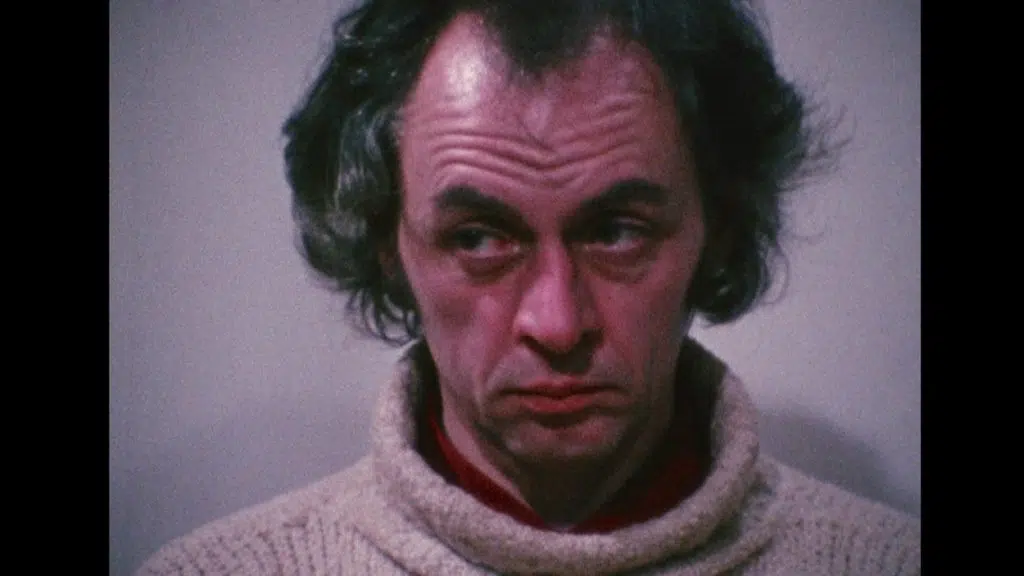

Among the patients we meet is David, an obviously disturbed man who attempts to dominate everyone around him with alternate displays of passive and aggressive behaviour. If one tactic doesn’t work, he switches to the other, keeping up a relentless commentary throughout on what’s going on around him. “Shut up, David,” most often uttered by fellow patient Julia in her heavily sedated voice, runs like a refrain through the early part of the film.

What to do about David? He’s disruptive, won’t respond and is ruining the therapeutic vibe. Send him to a proper “mental hospital” would appear to be the obvious answer, and watching therapist Leon Redler and his fellows trying to tiptoe around that one provides much of the fascination of the film, though to be fair to Laing’s ideas, Laing never rejected old-school therapy outright.

David is a buzzkill as a fellow inmate, but he does the film a great service, making obvious what’s going on here – psychiatry as countercultural argument. In a world where everything mainstream was automatically wrong, where everyone over 30 was suspect, here was the awkward customer making it obvious why governments still exist, and armies, and rules. Sometimes, if you let it all hang out, it all just falls out.

It’s easy to find fault with Laing, and he backed off a bit from some of his more relaxed (ie dogmatic) positions in later life, though what’s obvious is how grounded and gentle this house is. The patients interact to a large extent like a loving family (oh irony), they’re mutually supportive. This is an OK place to live and we do actually see people making strides in their ability to deal with the world – if the drugs don’t work, group therapy might.

We also get glimpses of what drove most of these bewildered, troubled people mad in the first place. Look out for Jamie, a posh young man crippled by a punishing lack of self-confidence, and then marvel when his father arrives, a man so ostentatiously, almost aggressively self-assured that it’s as if Laing had hired him to demonstrate his theories about the role of the family in producing insanity.

It’s all shot in early 1970s style – bright lights bouncing off gloss paintwork, the soundman getting in the way, a big camera you can hear whirring away most of the time, the echoey sound another staple of the era. The residents start out incredibly uneasy at the camera’s presence but soon adapt. It’s not out to exploit them. In fact the crew and the film fit in largely with the vibe of the place, a relic from a bygone age with a gentle lesson for the future.

Asylum – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2021