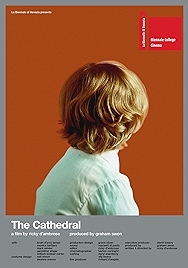

A film about a kid growing up, from 1980s birth to graduation, The Cathedral has Richard Linklater’s Oscar-winning, audience-slaying Boyhood to contend with. Which makes Ricky D’Ambrose’s debut feature even more impressive once you’ve seen it. The comparisons are still there, yet D’Ambrose has managed to make something recognisably operating in the same field as Boyhood and yet undeniably its own beast.

Partly that’s because this is D’Ambrose’s own story – semi-autobiographical says the publicity – or more generally the story of his family, who as a group expend much psychic energy on their own affairs and ongoing family feuds, rather less on the future of the family, as embodied in the figure of Jesse, who is played by two different actors, Robert Levey II at the age of about 12, William Bednar-Carter at 17/graduation age.

Like Boyhood it’s an episodic, scenes-from-a-life affair, except with an authoratative voiceover delivering facts – how Jesse’s parents met, for instance, how they interacted with other elements from his wider family and hers, how they eventually divorced. So cool and matter of fact is the voiceover, so high in the mix, that when the actors step forward to do their thing, the impression is of one of those reconstructed reality sequences you get in drama-documentaries. The voiceover states the facts, the actors add the colour. But only to an extent. D’Ambrose’s deliberately flat shooting style, of long static shots, artlessly artful compositions and “no lighting” lighting opens up a mid-point between the obviously artificial and the convincingly realistic.

What we’re watching are instructional moments, D’Ambrose appears to be saying, and we lean in the better to catch the lesson to be learned, even when the action seems to be of little consequence. Like Jesse’s dad angrily handing him money for his lunch which somehow becomes, again, a moment all about Dad rather than Jesse.

The “long” story, never quite stated but all the more forceful as a consequence, is that Dad Richard (Brian d’Arcy James) is no good, that in Lydia (Monica Barbaro) he’s accidentally snagged a woman who is better than him in most respects and who, eventually, is going to capitalise on the fact that other men are willing to keep her in a style which her own husband aspires towards but cannot reach. That makes him mad. No one ever sighs and mutters “bless” when Richard enters the room, but it hovers there in a collective thought bubble.

There are other psychodramas – the death from Aids of Richard’s brother just before Jesse was born, the shameful treating of one of Jesse’s grandparents, the barely concealed contempt of Lydia’s parents towards Richard, the ongoing feud which means some members of the extended family haven’t spoken in decades. Jesse features in none of them. We learn barely anything about him, or the other, incredibly peripheral, youngsters in this extended family absorbed in its own solipsistic weirdness. Tolstoy’s line from Anna Karenina that each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way seems apt.

D’Ambrose intersperses these everyday vignettes of a normally fucked-up life with ironic cutaways to adverts hung on the America of myth – a 1980s TV advert for a commemorative Liberty coin, another for Kodacolor Gold film that’s all about capturing those special moments with the nuclear family – but also reminds us of the way we were with archaeological relics from the pre-digital era. A picture book. A map. A brochure.

The total effect, assembled from all these reports from the margins and footnotes, is of a family of everyday awfulness locked so inside a mindset that they cannot see how they’re doing anything wrong. A critique of the boomers, for sure. You’ve got to wonder how D’Ambrose’s family reacted to it when they saw it. That “semi” in “semi-autobiographical” must have been working very hard.

The Cathedral – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022