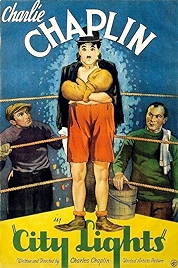

Charlie Chaplin started making his film City Lights in one era and released it in another. In the three years the picture was in production, an epochal shift occurred as Hollywood abandoned the silent movie and went wholesale over to talkies. When Chaplin started shooting what was intended to be his biggest picture to date in 1928 he was the king of the hill – and of the world, its biggest ever star before or since – in a world of silent movies. By the time he finished, Keaton and Laurel and Hardy and Harold Lloyd were all talking and the world was going crazy for the likes of Fredric March snarling his way through (much of) Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and Clark Gable and Joan Crawford whispering sweet nothings to each other in Possessed.

But it went even crazier for City Lights, which trumped them all to become the biggest grossing film of the year in the USA. A triumph, since against the advice of everyone he knew, Chaplin made City Lights as a movie without speech and with intertitle cards, the old-fashioned way.

Though technically it’s not a silent movie at all. The score (written by Chaplin) is part of the film – it is on the “sound track” running alongside the image – and there are a couple of other sounds, comic ones, on there as well, which is Chaplin essentially blowing raspberries at the concept of the talkie. Chaplin, a gloomy soul who’d first thought that movies were a passing fad when he got involved in 1914, also wasn’t convinced that the talkies would have legs. Chaplin was also gloomy about his career prospects now sound was here – rightly, this time. He sensed that the game was up, that his era was coming to an end and so put his all into what he wanted to be his magnum opus.

His efforts have been rewarded by the approval of fellow film-makers. Tarkovsky named City Lights his favourite film. Kubrick loved it too. So did Orson Welles.

If you’re not a fan of sentimentality, City Lights is possibly not for you, because it’s a 50-50 split of brilliant sight gags and a sappy love story played out between Chaplin’s Little Tramp figure and a blind flower seller (Virginia Cherrill), who mistakes the little guy for a rich swell, in a scene that Chaplin reshot more than 340 times in an attempt to get this key scene right. As part of the process he fired his star, then rehired her (she asked for twice the money, and since she had him over a barrel, she got it). You’d never guess by looking at it, a fresh and simple sequence involving Chaplin getting out of a car he shouldn’t have been inside in the first place, buying a flower and falling headfirst and utterly in love with the unattainable young woman.

This strand is one of the film’s throughlines and allows Chaplin to spend most of the rest of the running time in a series of gag-filled sketches, most notably the famous boxing scene, in which he, a prizefighter (Hank Mann) and a referee (Eddie Baker) dance a little comedy ballet as the Tramp tries to avoid being hit by his lumpfisted opponent by making sure the ref is always between them. Beautifully done, by Mann and Baker (uncredited, amazingly) as well as Chaplin.

The other throughline concerns the Tramp’s accidental friendship with a millionaire (Harry Myers) who he saves from suicide and so becomes the rich man’s drinking pal. Drunk they’re pals, anyway. Sober, the rich man has no idea who the Tramp is.

Both the squiff-eyed Myers and the fragrant Cherrill are perfect, but then all of the key players in this film are.

“A comedy romance in pantomime” Chaplin clearly bills it, right up front, as if to pre-warn audiences they’re not getting a talkie. Chaplin is the only person in this film still wearing old-school silent-movie make-up, a hand-me-down from vaudeville. Everyone else looks modern, in their 1930s fashions, while cars pile up and down busy streets that show no sign whatsover of the Great Depression.

The sight gags are not as elborately worked up as Keaton’s and Chaplin reuses the “wrong end of the stick” gag more than Keaton would have done, but his execution is exquisite. At 40 years old Chaplin was worried that his abilities as a physical comedian were on the wane. You’d never believe it watching City Lights.

City Lights – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022