The day I watched Cuties, 24 September 2020, it had 21,348 votes on the IMBD user ratings. 16,355 of those were one star reviews. And then I remembered that the film been caught up in one of those social media shitstorms, with its distributor the focus of a #CancelNetflix campaign. The overall 2.7/10 rating looked like the result of an orchestrated hit.

The campaign against the film drew support from across the political spectrum, though a trawl of Twitter suggests a lot of its supporters were outraged social conservatives. So much for Cancel Culture (a series of unrelated memes bundled together and then mis-sold as an actual culture) being an unsavoury aspect of the liberal/left (another grouping that doesn’t exist, but let’s not go into that here).

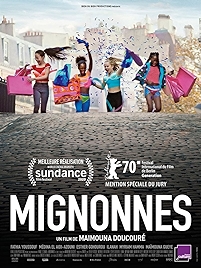

Had any of the voters seen the movie? It’s about a girl (the remarkable Fathia Youssouf as 11-year-old Amy) from a devout Islamic immigrant family who arrives at a new school in Paris, catches sight of precocious dancing dervish Angelica (the equally remarkable Médina El Aidi) – all legs, hair and moves – and busts a gut to be part of Angelica’s Mean Girls-y clique, who are all practising to be in a regional dance competition. Having being grudgingly admitted to the gang, Amy then surprises her hard-won new friends by introducing them to the more lurid end of the dance spectrum, moves Amy learnt from a smartphone she stole off her cousin.

It’s a story of a young girl trying to fit in, overdoing it, losing her personal integrity and going off the rails. It’s also the story of a group of young girls trying to be grown up and getting it all wrong. Yes, the girls’ dances are fairly gnarly to start with, and once Amy has worked various twerky, booty-focused, lap-dancy moves into the routine (including that one where you appear to be having sex with the floor) things move into jailbait territory.

The film has two trajectories, and they are expertly intertwined by writer-director Maïmouna Doucouré in her feature debut. Amy’s involves her and her outwardly stoic, inwardly devastated mother (Maïmouna Gueye) coming to terms with the fact that Amy’s Senegalese father is about to take a second wife and will soon be moving her into the family’s small apartment – a special out-of-bounds bedroom has even been set aside for the new bride. On the way to what Amy sees as a violation of her mother and the family home, Amy has her first period and is declared – by mother and auntie (Mbissine Thérèse Diop, star of Black Girl, the groundbreaking Senegalese movie from 1966) – to be “a woman”. You can understand why she’s confused.

The girls, meanwhile, head towards their dance competition, grinding and winding away, eager to be taken seriously as grown-ups though they’re only 11, blundering around in territory they think they understand because they’ve seen sexual material online. But just how naive they are is beautifully caught in a vignette where the girls are playing together and one of them (Esther Gohourou) inflates and plays with a used condom, mistaking it for a balloon.

Does the film feature young girls raunching away like little Lolitas? For sure. Does it suggest this is a good thing? Far from it. In fact Doucouré goes out of her way to underline just how far out of their depth the girls are. If the condom scene hasn’t done it for you, as the girls perform for an actual live audience Doucouré throws in numerous shots of women in the audience reacting negatively.

Girls growing up in a sexualised society is what the film is about. Talk about shooting the messenger.

The hoo-hah has at least got the film noticed. And it deserves to be noticed, not just as a polemic but also as a piece of great film-making. The smart screenplay does not call at the usual way-stations – there is no female genital mutilation, no misogynistic angry imans – the acting is fresh and believable, and the cinematography clean, bright and attractive. Doucouré has avoided the temptation to make things too “street”.

It’s a film about 11-year-old girls, after all, and though the girls are confused this lively, funny and ultimately optimistic film never is. Which is more than you can say for the haters.

© Steve Morrissey 2020