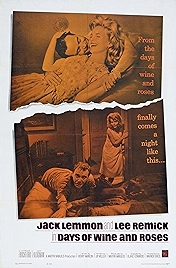

You might know the title Days of Wine and Roses from Ernest Dowson’s 1896 poem Vitae Summa Brevis – “They are not long, the days of wine and roses/Out of a misty dream/Our path emerges for a while, then closes/Within a dream”. Or you might know it from Johnny Mercer and Henry Mancini’s Oscar-winning theme song to this film, made famous by Andy Williams, whose lines replay Dowson’s sentiments. “The days of wine and roses laugh and run away like a child at play/Through a meadowland towards a closing door… etc”.

If you’ve never actually seen the 1962 film repurposing the phrase, it comes as a shock to discover that the “wine” Dowson and Mercer/Mancini were using metaphorically has been put to work literally in a highly strung drama about a pair of boozers dragging each other to the bottom of the bottle. Wine, ironically, is one of the few tipples they don’t go near.

The movie connects back to the great film about alcoholism, 1945’s The Lost Weekend, through its star, Jack Lemmon. The trail goes like this: Billy Wilder directed Ray Milland in The Lost Weekend. Wilder also directed The Apartment, which starred Jack Lemmon. Lemmon takes the baton on into Days of Wine and Roses, shot in a monochrome that’s reminiscent of The Apartment and with a deliberate callback to it in early scenes set in an elevator – where Lemmon met-cute with Shirley Maclaine in The Apartment, and makes a romantic breakthrough in Days of Wine and Roses with icy secretary Lee Remick.

He’s a PR guy with the everydude name of Joe Clay, she’s a bootstraps kind of gal who resists the advances of Joe after meeting him at a party where Joe, a PR fixer, had been brought in to provide girls to make the evening swing.

Joe likes a drink, so does everyone in his business – it’s a Mad Men kind of world. But Kirsten does not. Joe finds a way through her defences by ordering a brandy alexander for the chocoholic Kirsten. And before you can say sheets to the wind, both of them are seeing life through an upended glass.

From here it’s marriage and a (neglected) daughter and a race to the bottom, on and off the wagon, Joe discovering Alcoholics Anonymous after losing one job after another, Kirsten being reluctant to come along for the ride. She likes a drink, dammit, and cannot countenance herself as a common, dirty alkie.

Those early scenes between Joe and Kirsten – where he is essentially grooming her – make for uncomfortable viewing. And Joe’s little phrase – “Magic time” – uttered whenever he has the first drink of the day, also has an ugly ring of truth about it.

John Frankenheimer directed the 1958 TV version and you might have expected him to take on the film version too. Perhaps Frankenheimer was considered “too TV” – he’d never directed a feature at this point – and so the gig went to Blake Edwards, who’d just made Breakfast at Tiffany’s and so knew how to turn challenging material (Holly Golightly is a hooker, after all) into popcorn.

(Ironically Frankenheimer would instead direct, one right after another, three of the most brilliant monochrome movies of the 1960s – The Manchurian Candidate, Seven Days in May and The Train.)

Edwards sprinkles glitter where he can. This is a lush and gorgeous looking film, though there’s no attempt to hide the reality of boozing. Lemmon and Remick both veer into “stage drunk” territory occasionally – laughing excessively, wobbling overly – but the presence of AA founder Bill Wilson on the set as a consultant clearly had an influence. Alcoholism is presented as a grim condition, with both Lemmon and Remick getting moments to go all-in on the sort of physical acting that usually attracts Oscar’s attention.

Oscar kept his eyes averted, though the Academy liked the theme song, which never once mentions straitjackets or 12-step pledges. Maybe Oscar was right to – Days of Wine and Roses is hard going as “entertainment”, hard-hitting and ultimately depressing, in spite of the brilliant performances of Remick and Lemmon.

Days of Wine and Roses – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022