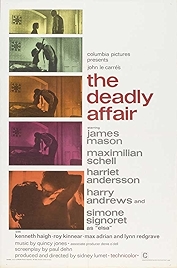

1966’s The Deadly Affair repeats the formula of The Spy Who Came In from the Cold – John Le Carré story, top British and European cast, London locations, great US director, ace British cinematographer, soundtrack by a big name – and if it isn’t quite up there with the 1965 film, it’s still one of the very best Le Carré adaptations.

It takes Le Carré’s first novel, A Call for the Dead, slaps a less sombre, more bums-on-seats title on it and also renames Le Carré’s masterspy George Smiley, as Charles Dobbs (Paramount, who had made The Spy Who Came In from the Cold, “owned” the Smiley name). Though in all important respects this is Smiley, an ageing, owlish penpusher with a wife called Ann (Harriet Andersson) whom he adores but who treats him like shit – she’s “a nymphomaniac slut” in her own words, and most of Dobbs’s colleagues would agree, since they’ve nearly all slept with her.

The plot hangs off the death of a ministry wonk. Suicide is the official explanation. Samuel Fennan (Robert Flemyng) was about to be outed as a former communist sympathiser, so the story goes, though Dobbs had quizzed Fennan on the very subject only that morning and Fennan had seemed happy to admit he’d been a Communist Party member in his university days – “Half the present Cabinet were Party men,” he points out. Unconvinced by the official line and suspecting murder, Dobbs sets about investigating, roping in Inspector Mendel (Harry Andrews), a cop on the verge of retirement, to help with the spade work. But first a trip to visit the dead man’s wife, Elsa. She is played by Simone Signoret, and let’s just say that you don’t hire Signoret simply to play the grieving widow.

James Mason’s mannered delivery works in his favour in The Deadly Affair. He’s a brilliant, silky Smiley (I mean Dobbs) – the silent but deadly quiet man whose unobtrusiveness is his secret weapon. The Dobbs character is of a piece with the shabby London settings captured by director Sidney Lumet. Far from the Swinging London of many mid-1960s movies, this is still the post-war world of damp rooms, electric fires and adultery, Lumet leaning in to Le Carré’s determination to present spying as a drab and morally ambiguous affair in much the same way Martin Ritt had in The Spy Who Came In from the Cold.

Lumet also wanted to shoot in black and white, as Ritt did, but was prevailed upon by the studio to film The Deadly Affair in colour. Cinematographer Freddie Young gets Lumet half the way there, though, by “flashing” the film (exposing the negative to a controlled amount of light), a technique that drains out the colour, knocks back the contrast and increases shadow detail. This is a murky film that plays out in one underlit, beautifully photographed interior after another.

It’s also a superbly made film in terms of Lumet’s economical direction. From the opening shot, of Dobbs and Fennan already in mid-conversation in St James’s Park, Lumet does not hang about but drives the story forwards.

What a cast. As well as Signoret and Andersson – both greats of cinema – there’s the Austrian/Swiss actor Maximilian Schell, now amazingly almost a cinematic footnote but at the time about as big a star as a non-anglophone actor could be in Hollywood. One of Lumet’s fascinations is the way different actors work in different registers. Against the bluff, four-square Harry Andrews there’s puckish, nervous Roy Kinnear, for instance, and Lumet also stages several scenes at the theatre, where yet another different breed of actor, brother and sister Corin and Lynn Redgrave, play a camp director and his over-eager stage manager. We even get extracts from the plays they are supposedly working on – Shakespeare’s Macbeth and, particularly, Marlowe’s Edward II, where David Warner is playing the king and Timothy West is a witness to his terrible death (red hot poker where the sun don’t shine). Lumet is obviously indulging himself in a bit of “what I did on my holiday in London” postcard-writing with these scenes from Royal Shakespeare Company productions but they also provide a bit of contrast with the drabness of Dobbs’s milieu.

Quincy Jones’s lush John Barry-like score (title song sung by Astrud Gilberto) does something similiar, acting as a stark contrast to locations like semi-industrial Lots Road in West London, in the days before all of the Thames waterfront had gone upmarket. It’s where Dobbs finally unmasks his “traitor”, the dénouement playing out, grimly, quickly, in the dark and the pouring rain.

The years have been kind to this film, coating it in an allure it didn’t obviously have at the time. Mason is a superb Smiley (Dobbs, whatever) and this is a superb Le Carré adaptation.

PS: do yourself a favour and watch a restored version of the film, like the Amazon Blu-ray one listed below. It’s really worth it to see the results of the remarkable Freddie Young’s “flashing” technique. So much darkness, but so much detail.

The Deadly Affair – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2021