One of those pre-Code 1930s comedies that comes wrapped in an aura, Design for Living can’t live up to the sell. It’s not funny, though there is the odd smirk, nor perceptive, unless a comedy about the fickleness of women is what you’re after

The aura comes virtue of the boys in the backroom. Noel Coward wrote the original play, then Ben Hecht came in and threw most of that away while working on his screen adaptation, in the process turning Coward’s urbane posh gents into a couple of impetuous workaday types – the Time Out London review called it a “tea cups to beer glasses” transformation, and that’s a neatly pithy way of putting it so let’s stick with that.

And once Hecht has done his thing, diirector Ernst Lubitsch takes over, and while his famous “Lubitsch touch” is frequently evident, and his camera is elegant and in the right place (one of those things that’s unremarkable unless wrong), there’s only so much to be done when the material itself doesn’t work.

The “design for living” that Coward was scandalising theatregoers with is the ménage à trois, and the threesome embarking on it as an idea are George, a penniless artist, Tom a penniless playwright and Gilda (prounounced throughout as “Jilda”), a commercial artist, there in Coward’s play as a way of engaging with the debate about art for art’s sake versus art for cash.

Having met-cute with Gilda on a train in France, both men fall for her and she for them. What to do? The men tussle and bicker, then Gilda suggests they should just all be platonic chums together, the three of them – “No sex!” she commands. And they, preferring to have a bit of something than a lot of nothing, agree to her terms – she’ll be their muse, but nothing more.

But fate intervenes and sends playwright Tom off to London, whereupon George and Gilda immediately fall into bed with each other. Some time later, Tom, now rich, returns from London to Paris. Gilda steams into him, and he into her. Then it’s George’s go again, until finally, exhausted by the chicanery, Gilda plumps for neither of them, and instead decides to marry safe, rich capitalist dullard Max Plunkett. Until she realises that that’s been a terrible mistake as well.

Edward Everett Horton actually gets the best of it as Plunkett, but then Horton was a class act who improved everything he was in. His Plunkett is small beer, though, a character designed to show how stodgy conventional morality was.

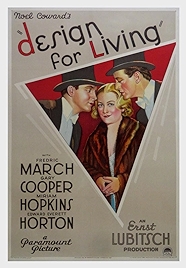

The leads hogging most of the camera’s time are Gary Cooper (George the artist), Fredric March (Tom the writer) and Miriam Hopkins (Gilda, the gal who can’t say no). Posterity has awarded Cooper with longevity (largely on account of films like Mr Deeds Goes to Town and High Noon), whereas March’s fame has receded with time, something two Oscars and two Tonys haven’t been able to hinder. As for Hopkins, you have to be an aficionado of films of this era to have any idea at all about who she is.

That pecking order is reversed in this film. Hopkins is head and shoulders better than the guys. Her character is smarter, which helps, but her acting chops and comic timing are better too. March comes in a limp second and Cooper way behind. Cooper is many things, but a comic actor isn’t one of them. If it wasn’t for his commanding physical presence his performance would be a thoroughgoing dud.

The actors aren’t the problem though, it’s the lack of beef. What is the story here? Where’s the dramatic friction meant to be when, at the first sign of being offered a new horse for her journey, Gilda leaves the old one at the staging post, swapping out Tom for George and George for Tom? Gilda, as Hecht has written her, isn’t a free spirit, a liberated woman, she’s a spoilt child, or a silly female who doesn’t know her own mind.

It soars here and there – the “touch” on display when Plunkett and Gilda go to buy a bed in a department store and Lubitsch does it all in dumbshow from outside, watching him and her through the display window while he measures the conjugal bed, then her, then himself.

And the DP is Victor Milner, who was Oscar nominated ten times and won once for the 1934’s Cleopatra, so it all looks fine, better than fine, especially if you’re watching Criterion’s sparkly high-def restoration.

A lot of people love this film, so I don’t expect there to be widespread agreement with this assessment. But I sat down to watch Design for Living expecting to be amused and delighted – after all, Coward, Hecht, Lubitsch, what could go wrong? I wasn’t.

Design for Living – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate