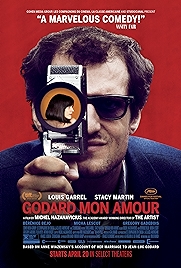

Le Redoutable aka Redoubtable aka Godard Mon Amour is another exercise in period spoofing for Michel Hazanavicius, the French film-maker who made his name with pastiches – notably winning an Oscar for The Artist, the faux silent movie having followed two 007 spoofs, the OSS 117 movies.

In all three a fictional character was held up for mild ridicule while Hazanavicius and his team sweated the small stuff, getting thousands of details just so in an attempt to conjure a world back into existence.

As with the OSS films the period this time is again the 1960s but this time the central figure isn’t fictional, it’s director Jean-Luc Godard, the hippest man in 1960s cinema, the Bob Dylan of the big screen.

Hazanavicius’s story picks up Godard (Louis Garrel) just at the point where he’s married the star of his latest film, La Chinoise, beautiful waif Anne Wiazemsky (Stacy Martin)– she’s around 20, he’s mid 30s – and follows them through the “events” of 1968 and out the other side, when their relationship collapses.

En route we see an eminently reasonable, fun and accommodating (and frequently naked) Wiazemsky contending with a difficult, withdrawn, argumentative, aggressive, needy, cold Godard. Beauty and the Beast, one representing cinema as entertainment, the other cinema as revolution at 24 frames per second.

Echoing Marx’s remarks on history repeating itself, the first time as tragedy, the second as farce, Hazanavicius replays the events of 68 – Godard and Wiazemsky on the streets, attending debates with students, disrupting the Cannes film festival – each time putting a lightly farcical spin on things. If Godard was the hero of his own narrative back then, he isn’t here.

Nor is he entirely at the centre of things. His not-so-glorious passage is seen through the eyes of Anne, and her sister in combat Rosier (Bérénice Bejo), another glamorous trophy of a successful artistic male, Bamban (Micha Lescot).

With a number of intervening decades between him and his subjects, Hazanavicius appears to be tentatively offering two real criticisms of the man. Godard fails to realise that he’s too old to be part of a youthquake, even with a hot young wife at his side. Perhaps even more to the point, he’s actually a member of the bourgeois class he’s railing against (as, for that matter, are the students tearing up the cobbles to throw at the police, but that’s another matter).

As soon as I saw those dark prescription glasses and thinning thatch I knew exactly who Louis Garrel was meant to be and that I wanted to see this film. He’s perfect as Hazanavicius’s fallible version of Godard. I’ve got no reference point for Wiazemsky but Martin (after Nymphomaniac another heroically underclad role for her) plays her as a smart, untutored young woman in thrall to a maestro she’ll eventually outgrow.

Godard hates this film. “A stupid, stupid idea,” he called it, and while it’s never going to have the mass appeal of The Artist, and there’s only so many impetuous sulks you can watch, there’s sport to be had watching Godard’s legend being adjusted – each of the chapter headings alludes to one of his films, for example.

You’ll be bored if you’re not into Godard, most likely, but Hazanavicius does try to head resistance off at the pass, with several scenes of pure Godard pastiche, fourth-wall this and meta-that, including the memorable one where Godard and Wiazemsky discuss the dramatic justification of on-screen nudity (“if the role demands it” etc) while both being naked for no reason except to poke fun at this sort of artistic piety.

Godard was wrong about cinema and revolution in the 1960s. The decade got its rocks off to music not pictures, though Godard continued up the cul-de-sac of “non-bourgeois” film-making to the point where his films became products of participatory democracy, with everyone involved having a vote on every artistic decision. Hazanavicius closes his film at the point where Godard, at work on a film, is forced to go along with one such democratically arrived-at decision, one he disagrees with. Close-up on the face of a man who’s theorised himself into an artistic dead end, hoist on his own farcically tragic petard.

Godard Mon Amour aka Le Redoutable – watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2020