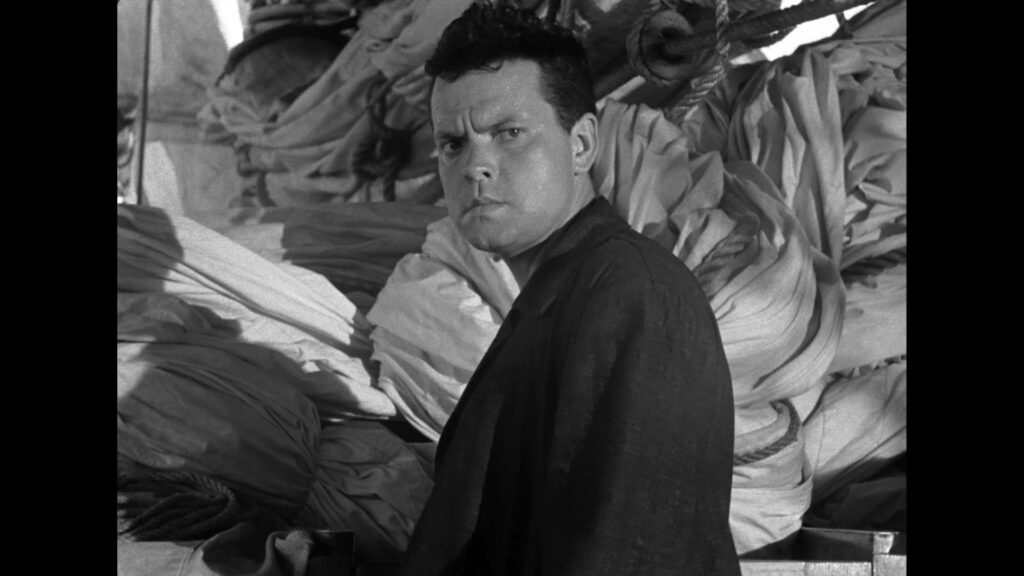

Early on in The Lady from Shanghai there’s a key piece of dialogue explaining the title. Orson Welles’s Michael O’Hara, an Irish sailor between jobs, meets a woman (Rita Hayworth, Welles’s wife at the time) in New York. Michael is on foot, Elsa is in a horse-drawn carriage taking a turn around Central Park. In clear “I am hitting on you” dialogue, he charms her with stories about all the wickedest places in the world he’s been to. The Far East is high on the list, with Macau and Shanghai among the places mentioned. Elsa’s been to both those cities and a few more on his list besides. Gambling? he offers. Kind of, she shrugs.

The “lady” is no such thing, of course, but whether she can be more than one thing is really what this film is about. Or it would be if Welles’s original vision had been left intact. The studio reshot whole sequences, shortened the film in draconian fashion, added a histrionic score Welles hated and spent an entire year re-editing it to try and turn The Lady from Shanghai back into the sort of Rita Hayworth vehicle they thought they had been getting in the first place.

Welles had given them a kinky, vaguely Brechtian, darkly ironic The 39 Steps – man shackled to blonde, except this blonde is no innocent.

The original story survives in the mutilated version we have today. Michael is hired as crew on the yacht owned by the Elsa’s husband, rich lawyer Arthur Bannister (Everett Sloan), a man who needs sticks to get around. As Bannister, Elsa and Michael sail around the Caribbean, through the Panama Canal and up to San Francisco, she spends her time smouldering at the hired hand, while Michael gets through a lot of asbestos underwear in a vain attempt to keep her at bay. Meanwhile the husband glowers impotently. Also along for the show and trying to keep a lid on things, Broome (Ted de Corsia), a private detective, and Grisby (Glenn Anders), Bannister’s business partner.

On top of this romance/not romance plot hinging on whether Elsa is or is not an out-and-out gold-digger, there’s a bizarre murder/not murder plot. The incessantly sweaty Grisby suggests it to Michael out of the blue, laying out the plan to bag a massive insurance payout when Grisby “dies”, from which Michael will get $5,000, enough to buy Michael’s way into Elsa’s mercenary heart.

Is Elsa really a mercenary? Could Michael be a real killer? Does Grisby have an added motive? It all ends up in court, on a murder charge, where, bizarrely and in a Kafa-esque turn, Elsa’s husband is the prosecuting attorney. At one point he even calls himself as a witness in scenes clearly designed to be comical.

What a mess this film is, as off-kilter as Welles’s Oirish accent, and who knows what it would have been like in its intended form. Though there’s a kind of poetic justice in the mess it’s become since Welles is at some level interrogating the idea of the authentic individual, starting with Hayworth’s image – dyeing her hair blonde and cutting it short when she was famous for long, auburn locks – and working on through the cast. This instability of the personality is iconically summed up in the famous Hitchock-meets-surrealism finale, at a funfair, where a hall of mirrors reflects back multiple versions of the same character.

This sequence remains superb, as so much of the film is. The studio hated the fact Welles had dyed their star’s hair, they bemoaned the lack of glamour close-ups (and it’s very obvious where they’ve later been dropped in), and they also didn’t go a bundle on Welles’s decision to shoot on location, in handheld rough-and-ready style. Welles throws in some superbly elegant long tracking shots with much use of the crane, as if to buy the studio off with some wow factor here and there, but the sense is that he really wants to be out on the yacht (Errol Flynn’s in real life), on the high seas and in foreign climes.

It’s another case of what could have been, a Welles film, like The Magnificent Ambersons or The Stranger, to be watched as much for what’s not there as what is.

The Lady from Shanghai – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2023