It’s likely that nothing is ever going to knock Loving Vincent off the top spot when it comes to films about the paintings of Vincent Van Gogh. Whether it relegates 1956’s Lust for Life – which starred Kirk Douglas as the tortured artist – into second place as a biopic is another mattter entirely.

It’s a Polish movie with British/Irish actors in most of the key roles and an unashamed Citizen Kane structure. Douglas Booth takes the investigative role as Armand Roulin, the rough postmaster’s son trying to return a letter sent by Vincent to his brother Theo, and in the process going from one person to another, talking out of each details about the last days and weeks of Vincent’s life.

These come in flashbacks from Vincent’s early days right up to his death aged 37 of a gunshot wound, but the film is most concerned with Van Gogh’s last days in the village of Auvers, where he produced vast amounts of work and where the locals viewed him either as an unhinged madman or a genius in the making.

There is a definite murder-mystery aspect, with writer/directors Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman dropping hints early on that there was something suspicious about the shooting. Van Gogh’s psychoses are played down – there are scant references to his mental health or his time spent in the asylum, and the notorious ear-cutting (he gave the severed bit to a woman he was out to impress) is barely mentioned. Roulin’s investigation does raise questions. Not least that shooting yourself in the stomach is not only actually pretty hard to do but a terrible way of committing suicide. Van Gogh relationship with the local doctor is also worth looking into further. Why did Doctor Gachet make no attempt to remove the bullet from Van Gogh’s abdomen? It took Van Gogh two days to die. The doctor, one of the few who recognised Van Gogh’s abilities, swept in shortly afterwards for the art.

But was foul play actually involved? Kobiela and Welchman raise the idea only to let it drop.

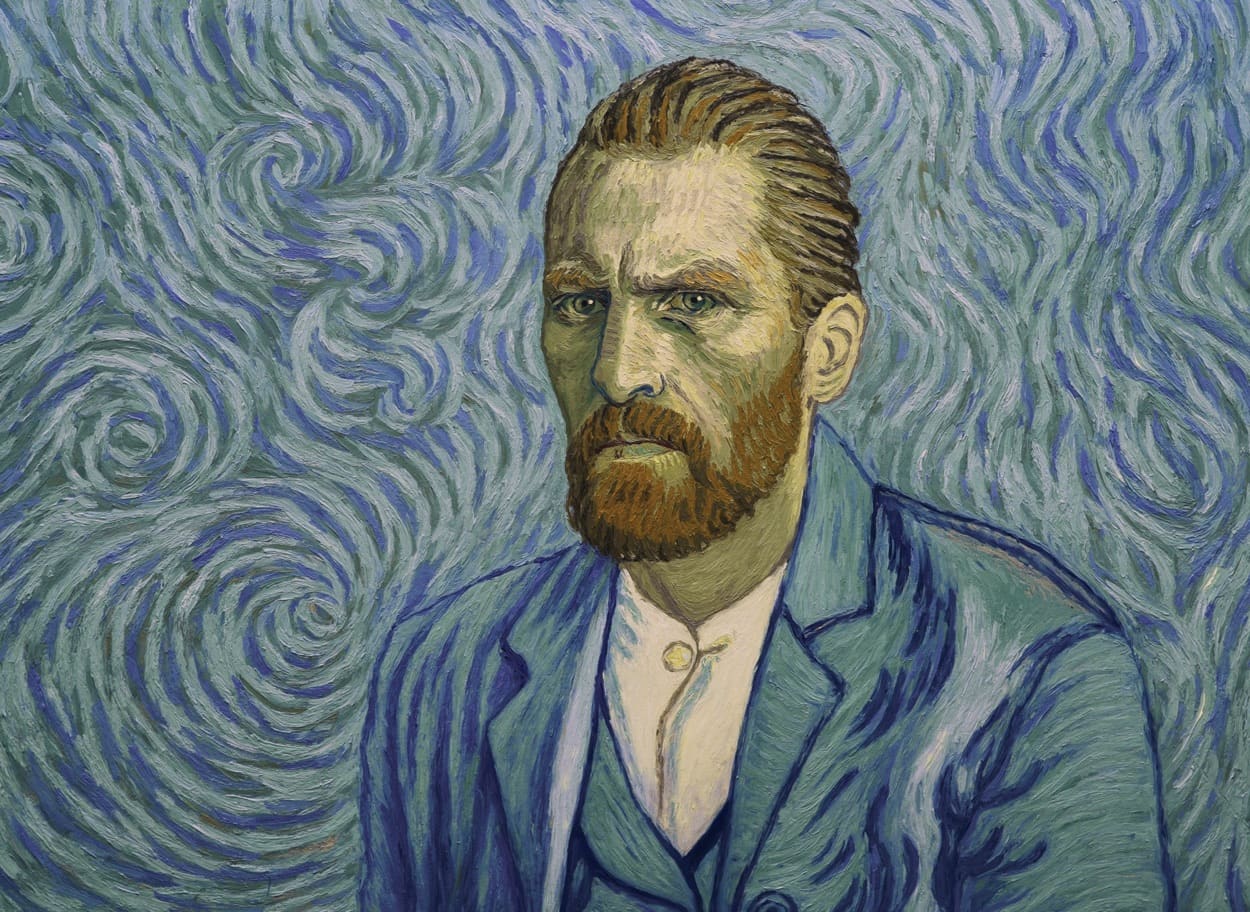

That’s largely because they’re focused on getting the look of the film right, an attempt to reproduce in moving images the style of Van Gogh’s work. To do this they hired teams of painters – specifically painters, not animators – around 125 of them to rotoscope the film. The “rotoscoping” technique was invented by animator Max Fleischer in 1915 and involves drawing or painting over the film, one frame at a time. Its great advantage is the fluidity of movement in the finished product. On the downside, it takes a lot of time and skill. Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was rotoscoped and so, more recently (and more digitally), were Richard Linklater’s Waking Life (2001) and A Scanner Darkly (2006).

The years of work have paid off. Van Gogh’s emphatic brushstrokes and his way of reproducing light and shade lend themselves to the treatment and the visuals pop off the screen. Kobiela and Welchman drop in the artist’s greatest hits as backgrounds – here a Starry Night, there a Café Terrace at Night, or a Wheatfield with Crows – which gives Loving Vincent a playalong aspect. Shout when you spot one you know. For the flashbacks into what Roulin’s investigations revealed about Vincent’s last days, a more sober black and white animation technique is used, which brings to life old photographs. It’s also effective, slightly dreamy, and suggests there’s more than one string to Kobiela and Welchman’s artistic bow.

Oddly, considering how it’s been made, the film isn’t that interested in how Van Gogh made his art or what he thought he was doing with paint that marked him out as different from other artists. This is a biopic about the man more than the artist. Perhaps, you’d argue, the visuals are telling us all we need to know. Perhaps so, but I’d have liked more, especially when what is revealed about the man doesn’t go very far either. Van Gogh remains largely an enigma.

The end credits reveal how close the cast are in looks to the originals – Chris O’Dowd as Roulin’s postman father, Jerome Flynn as the murky Dr Gachet, Saiorse Ronan as the doctor’s daughter, the innkeeper (Eleanor Tomlinson), Gachet’s housekeeper (Helen McCrory), the local boatman (Aidan Turner) – and paintings made for the film were on sale at lovingvincent.com. There are still prints, apparently. Worth having.

Loving Vincent – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2021