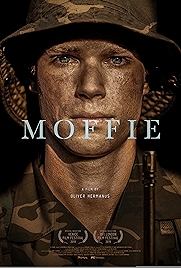

Strange film, Moffie. As if Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket had been crossed with Claire Denis’s Beau Travail, the brutal training discipline of the former with the shimmering lust-in-the-dust poetics of the latter.

But first the first – it’s 1981, we’re in South Africa, and the apartheid regime, not content with waging war at home, is conscripting its young men to do two years national service to fight wars against “communists” (ie black people) on its borders. As the film opens we meet Nick van der Swart (Kai Luke Brümmer), a nice-looking lad taking leave of his family and heading off to do his time in army fatigues.

The atmosphere is Full Metal Jacket – jockish, rowdy, masculinity rampant, racist, sexist, gayist. “Moffie” is the largely Afrikaaner-speaking soldiery’s term for anyone considered soft, effeminate, unmasculine, homosexual. Nick is quiet and fine-featured but he fits in well enough with his fellow conscripts, keeps his head down and gets on with the training regime led by tough-as-nuts Sergeant Brand.

Nick is gay but the film is slow to tell us that. It’s a fact not an issue, but a fact Nick isn’t going to broadcast around the camp, especially as two soldiers caught in a compromising situation in the men’s toilets have since been severely dealt with, as a punishment and a warning.

The pitiless training – the process of your individuality being broken and then being reassembled as a tough, unthinking fighting machine – is familiar, with Hilton Pelser’s Sergeant Brand joining the ranks of drill sergeants headed by R Lee Ermey’s Gunnery Sergeant Hartman in Full Metal Jacket and Louis Gosset Jr’s Sergeant Emil Foley in An Officer and a Gentleman as a taskmaster with an unsentimental streak a mile wide and a florid command of the put-down.

And then a sudden switch of gears. Full Metal Jacket becomes Beau Travail and the recruits are no longer grim-faced, pain-wracked automata but semi-naked young men filmed in slo-mo as they leap and stretch in a game of volleyball. The camera slides down Nick’s soft cheek, which is bathed in a golden-hour glow. And then, as if remembering what it is and where it is at, that moment is over and we’re back with the grunts.

There have not been that many examinations of homosexuality in the army. And it’s not exactly “examined” here either. But in Nick’s brief amorous entanglement with another recruit, director and co-writer Oliver Hermanus does start unpicking some of the military’s antipathy to homosexuality.

Homophobia is a term bandied about loosely and is often misapplied to people who don’t fear homosexuality, which is what the word means literally, they just don’t like it. The army, though, does actually fear homosexuality. It is a threat to an order based on a particular sort of physicality and a particular sort of masculinity and it also looks like a challenge to authority – asserting your individuality is not what the army is about.

Ironically and perhaps unexpectedly, this is the one thing Nick never quite does. The film is based on the real-life memoir of André Carl van der Merwe and its lack of a Hollywood moment – the “this is who I really am” bit – moves it out of message movie territory and into a more nuanced and less instantly gratifying place.

The Beau Travail moment is brief and Moffie‘s ruminations on sexuality are parked before the action heads out into the traditional final act – the guys head out to the conflict zone where their training and their essential nature is tested. Nick is no coward, he acquits himself well. The stonefaced Sergeant Brand, who has long since worked out what flicks Nick’s switches, grimaces at him and makes an approving cluck. The man? His heroics? His sexuality?

Demobbed, Nick meets his parents. They also seem relieved that the army has made a man of Nick. Or is it that their gay son now has nothing more to prove in the department of masculinity?

Don’t ask, don’t tell – as the US Army policy formulated it in the Clinton era. The question marks pile up. Ambiguity is Moffie’s stock in trade. The answers hover, much as Nick has hovered, just slightly out of reach.

Moffie – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2021