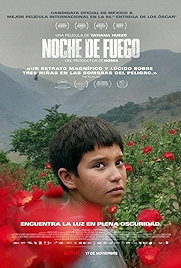

Writer/director Tatiana Huezo drops us straight in to Prayers for the Stolen (Noche de Fuego). As a dark screen accompanied by rapid breathing yields to a daytime scene of two females digging what looks like a shallow grave, the internal interrogation starts – Who are these people? Where are they? Is it a grave? Why do they both look so frantic?

No voiceover tells us, no “useful idiot” arrives on the scene to act as a conduit from screen to viewer. Huezo forces us to work it out. She’s a director with a background in documentary-making and this adaptation of Jennifer Clement’s best-seller uses a classic technique of the observational style. What makes Prayers from the Stolen stand out is the way that Huezo allies that technique with a keen eye for the aesthetic and a strong sense of narrative drama.

They’re digging a hiding place, not a grave, and as time goes by it becomes apparent that this mother and daughter in a backward Mexican village are living under constant threat. There are only two employers in this area – the quarry and the cartel, which organises the harvesting of poppies for the production of heroin. The quarry employs a few men, who drill and set explosives and blow the sides of mountains clean off. But not enough to compensate for the obvious lack of men in the village. There are none, apart from a couple of old guys and a teacher, who seems to have been bused in from outside.

Where the rest of the men have gone is never explicitly explained, like so much in this film. And what the women are afraid of can only be pieced together from a hint here, an event there – at one point Rita (one of the two digging females) takes her pretty daughter, Ana (the other one), to have all her hair cut off, so she looks less like a girl. Ana’s pretty friend Paula gets the same treatment but the other friend, Maria, doesn’t, but then Maria has a hare lip, a cloak of invisibility when the cartel guys come calling. At another, Ana applies “lipstick” – beetroot juice – to her lips and Rita tells her that she’ll knock her teeth out if she does it again.

Prayers for the Stolen follows Ana, Paula and Maria (but mostly Ana) from the age of about eight up to puberty, doing the things young girls do – school, mimicking their elders, mock-fighting with boys – and leaves the dramatic eventuality (inevitability?) of the cartel’s recruiting sergeant’s call just hanging there. Like Chekhov’s gun, that hole Rita and Ana were digging is going to be pressed into service at some point.

Huezo has an eye for the aesthetic, and this is a good looking film, thanks to subtle beauty lighting by DP Dariela Ludlow and the use of picturesque, almost National Geographic-like, imagery – like the villagers in the evening all standing on the hill trying to get a smartphone signal, the screens glowing like fireflies. Or Ana squatting by an outhouse whose walls of faded paint and door of distressed wood are picture-postcard shabby chic – if you don’t live in the village. Just plain shabby if you do.

Making hardship, ugliness and unbearable situations look glam – poverty porn – is Huezo’s potential problem, but she largely ducks it by amplifying the sense of threat from the cartel. They swish by in convoys of cars, like displaced Nazis, or whirr by overhead in helicopters, a faceless and largely offscreen presence.

It’s an intimate film and the relationships feel real, the girls to each other, Rita and Ana. The casting is brilliant in this respect, so good in fact that when the girls all suddenly age a few years, the new actresses playing girls who were eight a minute ago but are 13-ish now, appear to be the same people a few years on – they’re not.

In a more Hollywood film the local schoolteacher, something of a firebrand who wants to help this village escape the cartel’s grip, would be worked up into more of a character and more of a story. But this isn’t that sort of film. Happy ending not guaranteed, though gripping drama is.

Prayers for the Stolen – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2021