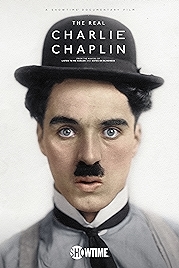

The most significant point that the documentary The Real Charlie Chaplin makes is that Chaplin wasn’t just the most famous man in the world from an early stage in his career, he was also famous in a way that had never happened before – planet-wide recognition, mass hysteria, factories pumping out merchandise, fakes pirating his act etc. The first global star of the age of visual media, this poor boy from London found success through Hollywood in an industry he only reluctantly joined thanks to the universality of silent movies. Chaplin’s fame outlasted his film career and his mortality. Like Mickey Mouse, a silhouette is enough to identify Chaplin.

The “Real” bit of the title suggests we’ve been wrong all this time about some aspect of the man and yet for the most part this is a straightforward run through of the authorised version of his life. Born to poor showbiz parents in London in 1889, the same year as Hitler and the pizza margherita, Chaplin was raised by a lone mother, who ended up in an asylum. Spotted by US entertainment impresario Fred Karno, he headed to the US where three shows a day in the English Music Hall shows honed acrobatic skills that translated perfectly to the screen when Keystone Studios producer Mack Sennett eventually offered him a gig on screen. Chaplin accepted reluctantly, fairly certain he’d be back treading the boards within a year.

His screen debut was 1914. Realising he wasn’t cutting through, later that same year Chaplin put together the Little Tramp outfit – Fatty Arbuckle’s trousers were just one element in a hand-me-down assemblage – and there the familiar figure is winking at us on screen in his debut, Kid Auto Races at Venice. The rest, as we all know, is history.

One of this documentary’s claims to specialness come from the access that film-makers Peter Middleton and James Spinney had to the Chaplin archive in Switzerland. None of the Chaplin family appear on screen, but we hear their voices. Middleton and Spinney’s real coup is getting hold of the 1983 audio interview that the film historian Kevin Brownlow did with Effie Wisdom, a childhood friend of Chaplin, and which is dramatically reconstructed with actors acting as placeholders. Plus a Life magazine interview, never previously aired, done with an old but still wary Chaplin in Switzerland in 1966, also dramatically reconstructed, with photographs from the interview dropped in to add flavour.

The reconstructions work well. More broadly, Middleton and Spinney’s research is excellent and the footage they’ve dug out and restored is superb. Some moments are very telling, like that glimpse of Chaplin with Mahatma Gandhi, which gives some idea of his fame (he also met Einstein, but that’s not in this film).

Missing is a journalist’s hand – there’s a maddening lack of timeline and context (who? when? where?) throughout, tiny details that would have helped to orientate the traveller. When did Chaplin build his own studios, for instance? It was 1918, information missing from the film.

Unsure where to pitch itself – at the knowledgeable fan or the know-nothing – though with so many angles to choose from that Middleton and Spinney must be given some dispensation, the film is, however, particularly good on Chaplin’s refusal to abandon silent movies long after everyone, Keaton, Laurel and Hardy and Harold Lloyd included, had gone over to sound. And how the writer/director/producer/composer/star went on to have some of his greatest successes, like City Lights (1931) and Modern Times (1936), in an era when audiences weren’t supposed to be paying to see silent movies any more.

There’s also a decent attempt to situate Chaplin culturally. The silent, playful Chaplin as the avatar of the oppressed. Universal. Sometimes gender fluid (in women’s clothes, complete with moustache). Sometimes sex-fluid (nancying about, often with policemen). All things to all people. And how this also sometimes counted against him when other labels – Jew, Communist, Homosexual, Subversive – were attached by those on his own side (the paranoid FBI) and elsewhere (the Nazis had a particular hatred, even before Chaplin parodied Hitler as “Adenoid Hynkel” in 1940’s The Great Dictator).

There’s a cakeist approach to the problem of the young women, which the film acknowledges only in a half-hearted way. The marriages to teenage girls, the many affairs with even more and even younger teenage girls, the many forced abortions.

Tell-all moments include ex-wife Lita Grey Chaplin spilling the beans on how horrible Chaplin had been to her. He’d married her when she was 16 and pregnant, after failing to convince her of the benefits of a termination. In footage from 1966, we see Lita telling her interviewer that she’d met him when she was playing the uncredited Flirtatious Angel in his film The Kid. She was 12 years old. She pauses, significantly. We fill in the blanks. There’s a whole documentary to be had from this aspect of Chaplin’s life alone, and not a particularly edifying one.

Having been chased out of the US by the McCarthyites, Chaplin spent the last 20-odd years of his life in splendid isolation in Switzerland, in a final marriage to Oona (daughter of playwright Eugene) O’Neill. Late footage of Chaplin entering his declining years in opulent exile is sweet. There he is in home cine footage larking about in the garden with his kids, who in voiceover tentatively voice criticism of their distant dad – “My father wasn’t Charlie Chaplin,” says Geraldine Chaplin. “Except when he had an audience. Then he’d become Charlie Chaplin.” Jane Chaplin found it hard to have a conversation with him. Michael Chaplin was “kind of frightened of my father.”

Documentaries usually make a decision, or have it thrust on them, to be either about the work or the person. The Real Charlie Chaplin manfully tries both and achieves neither. There is so much to say about Chaplin that perhaps this was always going to happen. Even so it’s a genuinely interesting documentary both about the man and a large chunk of the 20th century. Full of fascinating factoids, it reminds us that, right at the point where the current concept of stardom was being forged, Chaplin was there, the man, the monster and the towering talent. He remains, universal still, the template for everything that followed.

The Real Charlie Chaplin – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022