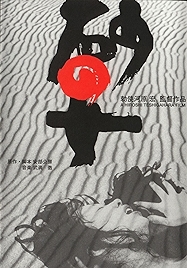

Whether you call it Woman in the Dunes, Woman OF the Dunes, or go with the original Japanese title, Suna No Onna, Hiroshi Teshigahara’s wildfire success from 1964 (arthouse wildfire – it’s relative) is surely unique in being the only absurdist erotic Japanese drama.

Tarkovsky rated it as one of his top ten films, and you can see why from almost the first shot, which announces that there’s going to be less a narrative, more a poetic approach to the storytelling with an image of a boulder that in fact turns out to be – as the camera pulls back, back, back – just one among millions of grains of sand, sliding, flowing, rolling relentlessly downwards. Tarkovskian, we might now call it.

The movement is ironic, because the film is all about being stuck, physically, and with the pitiless and pointless repetitive stasis of the human condition – as set out in Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus, which asks how humans should face an existence of utter repetitive futility (by lightening up, dude?).

Simple plot. An entomologist (not named until the end, when it turns out that Eiji Okada has been playing a man called Niki Jumpei) collecting bugs in sand dunes misses his last bus back to Tokyo and is helpfully guided by a passing local villager towards overnight accommodation in the home of a local widow, who lives at the bottom of a hole Niki has to reach by rope ladder.

“Old hag,” the villager ungallantly calls out to her, as he guides Niki down the ladder and into the home of the woman, never named. She’s not an old hag at all, rather a pretty young woman whose eyes seem to feast hungrily on the new arrival, whom she feeds and waters and entertains, positioning an umbrella over the table while he eats to keep off the sand, which never stops sifting into the charmingly and rather artisanal dwelling.

He awakes the next morning and is greeted by the sight of the sleeping naked body of his host across the room, her skin speckled with sand. He prepares to leave, only to find that the rope ladder has been pulled up. And there he stays, in what he instantly realises is a trap, in spite of attempts to escape, eventually falling in with her in her nightly task of digging sand, putting it into boxes and then sending the boxes up to the villagers, who wait up top, and reward the diggers with food, water and “rations”.

While they sleep more sand pours down, and so the next day the task repeats, ad infinitum, ad absurdam. See Becket, Ionesco or Pinter, or any number of plays featuring two people stuck on a stark set addressing the pointlessness of human existence in a world without god. You could also look to TV and Patrick McGoohan’s The Prisoner – man trapped by villagers, no idea what they want, no means of escape – the cult hit of three years later. He’d surely seen Woman in the Dunes.

There’s Bergman, too, in the deep focus stark cinematography of DP Hiroshi Segawa, whose background in documentaries serves him well in this confined space, though he’s also got a keen eye for the many varied textures of sand. There’s a lot of it.

Torû’s Takemitsu’s score is particularly effective. “Mocking” is how Roger Ebert described it. Yes, but also exclamatory, ejaculatory – look at this, look at this, look at this, it seems to shriek, howl and roar at key moments when the tension is mounting.

That’s the remarkable thing about this film, in fact. Considering how simple the setup – two people, one location – it is a tense film, skilfully constructed so the psychological pressure is always mounting, until, in a bizarre confrontation between the villagers at the top of the hole and him and her at the bottom, things come to a climax in a scene of frenzied music, whipcrack editing and high emotion I won’t ruin by explaining too much.

They’re a fine pair of actors, him and her. Okada expertly playing the naive, sexist bug hunter being introduced to a few home truths about the world and his privileged place in it as the story progresses, and learning what it is to be as stuck as one of his boxed and pinned insect specimens. Kyôko Kishida is even better as the more complex Woman – simple but not a simpleton, wanton but not loose, resigned to her fate, but out of a love for where she lives rather than meek acceptance. She’s the response to Camus’s question.

Watch the Criterion version, if you’re going to watch it. The 2016 release is restored and sees the movie back to its original 147 minute running time, rather than the shorter theatrical version that earned Teshigahara an Oscar nomination, the first Japanese director to have got one, amazingly, considering Ozu and Kurosawa were working at full power at the time.

Perhaps even more amazingly, Raquel Welch bought the rights in the 1970s, with a US remake in mind. It never happened. What might have been.

Woman in the Dunes – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022